Hooray for Flicker Alley releasing Laurel & Hardy: Year One, a beautifully presented 2-disc Blu-ray set of Stan and Ollie’s 1927 films. The all-new restorations look stunning, meticulously assembled from the best available materials contributed by archives and collectors around the world. I was honored to present a bonus video essay providing an overview of the locations appearing in several films, showing how Stan and Ollie made humble Main Street in Culver City their cinematic home. As fully explained in this post below, many Duck Soup locales require more diagrams and explanation than feasible for a brief visual essay, so my bonus program encourages interested viewers to check out this blog instead for more details.

Hooray for Flicker Alley releasing Laurel & Hardy: Year One, a beautifully presented 2-disc Blu-ray set of Stan and Ollie’s 1927 films. The all-new restorations look stunning, meticulously assembled from the best available materials contributed by archives and collectors around the world. I was honored to present a bonus video essay providing an overview of the locations appearing in several films, showing how Stan and Ollie made humble Main Street in Culver City their cinematic home. As fully explained in this post below, many Duck Soup locales require more diagrams and explanation than feasible for a brief visual essay, so my bonus program encourages interested viewers to check out this blog instead for more details.

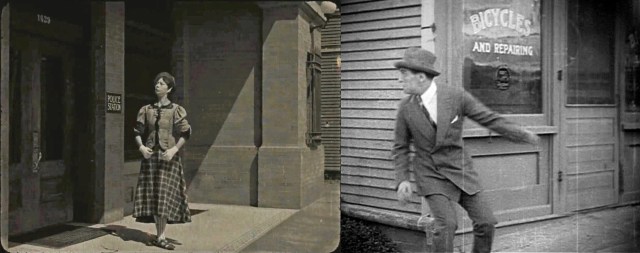

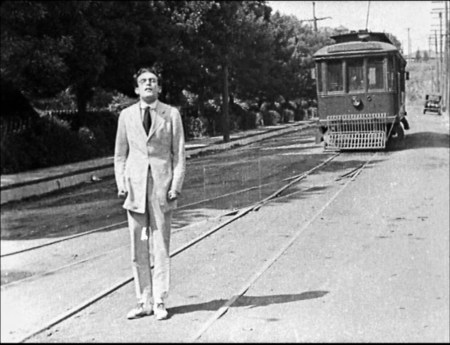

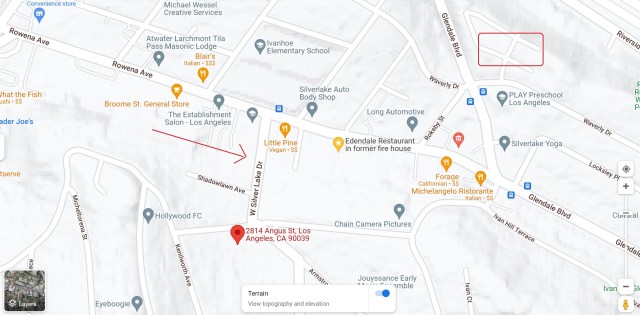

Although they had appeared onscreen together in The Lucky Dog (1921), the Hal Roach short Duck Soup (1927) marks the first time Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were paired as comedy leads. They play a couple of hoboes who flee a surly forest ranger conscripting tramps to fight a raging fire. The film begins in Westlake (now MacArthur) Park, where they dash off, grab a bicycle in Culver City, pedal up and down Grand Avenue in Bunker Hill, only to crash in front of a Beverly Hills mansion. This post examines the many classic landscapes appearing in this landmark film.

Although they had appeared onscreen together in The Lucky Dog (1921), the Hal Roach short Duck Soup (1927) marks the first time Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were paired as comedy leads. They play a couple of hoboes who flee a surly forest ranger conscripting tramps to fight a raging fire. The film begins in Westlake (now MacArthur) Park, where they dash off, grab a bicycle in Culver City, pedal up and down Grand Avenue in Bunker Hill, only to crash in front of a Beverly Hills mansion. This post examines the many classic landscapes appearing in this landmark film.

Forest rangers scour Westlake (MacArthur) Park, looking for bums to fight the fire, with a matching view seen from the other side looking to the NW at right LAPL. It appears the awning shaded a seating area for concerts performed in the pergola standing in the water.

At left, Joe Cobb looks toward the lakeside shaded seating area in the Our Gang comedy Dog Heaven (1927), with a matching color postcard view, LAPL, and closer view of the forest rangers grabbing bums.

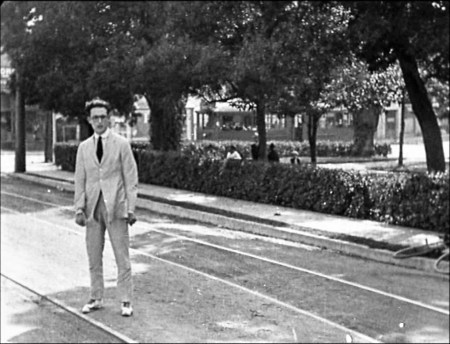

Ollie cheerily greets the menacing forest ranger played by Bob Kortman.

Stan and Ollie casually saunter away, followed by the ranger, who tracks their every step as they begin to flee. This was likely filmed in the NW corner of the park, with the now-demolished Regent Apartments peeking over the trees at back. For comparison the same corner of the park revealing the Regent appears to the right in this scene from Lige Conley’s 1920 short A Fresh Start. The Regent (1913-1983) appeared in many films, and portrayed the facade of the restaurant where Charlie Chaplin worked in The Rink (1916), inset, read more HERE.

Stan and Ollie casually saunter away, followed by the ranger, who tracks their every step as they begin to flee. This was likely filmed in the NW corner of the park, with the now-demolished Regent Apartments peeking over the trees at back. For comparison the same corner of the park revealing the Regent appears to the right in this scene from Lige Conley’s 1920 short A Fresh Start. The Regent (1913-1983) appeared in many films, and portrayed the facade of the restaurant where Charlie Chaplin worked in The Rink (1916), inset, read more HERE.

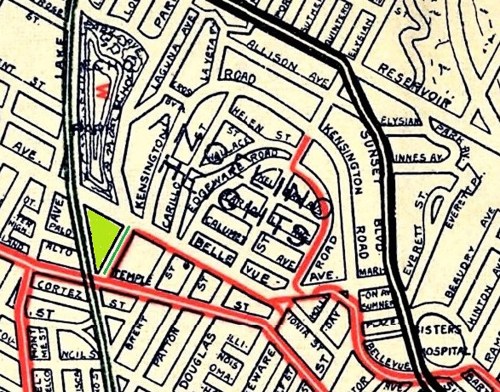

Looking at the NW corner of the park, with the lawn (oval) where the ranger likely chased the Boys in relation to the Regent – LAPL, USC Digital Library.

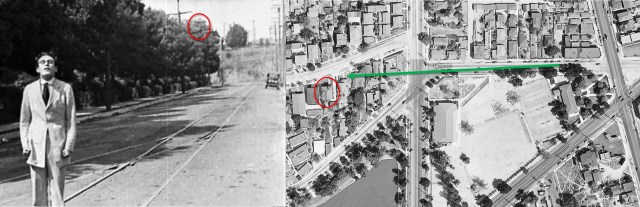

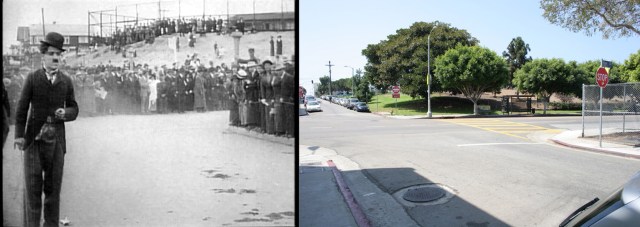

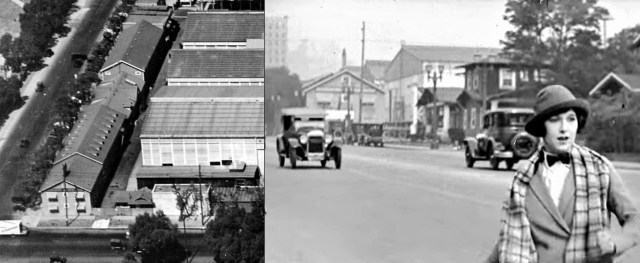

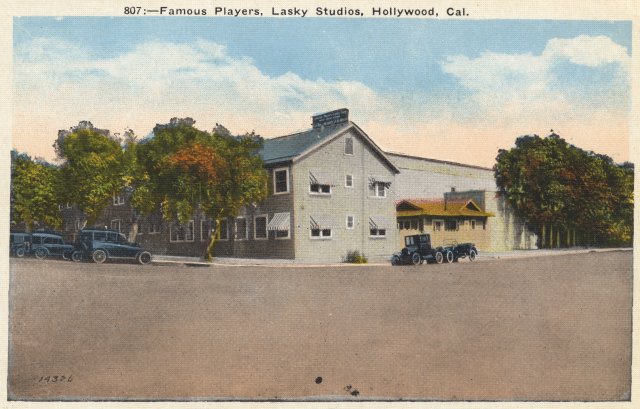

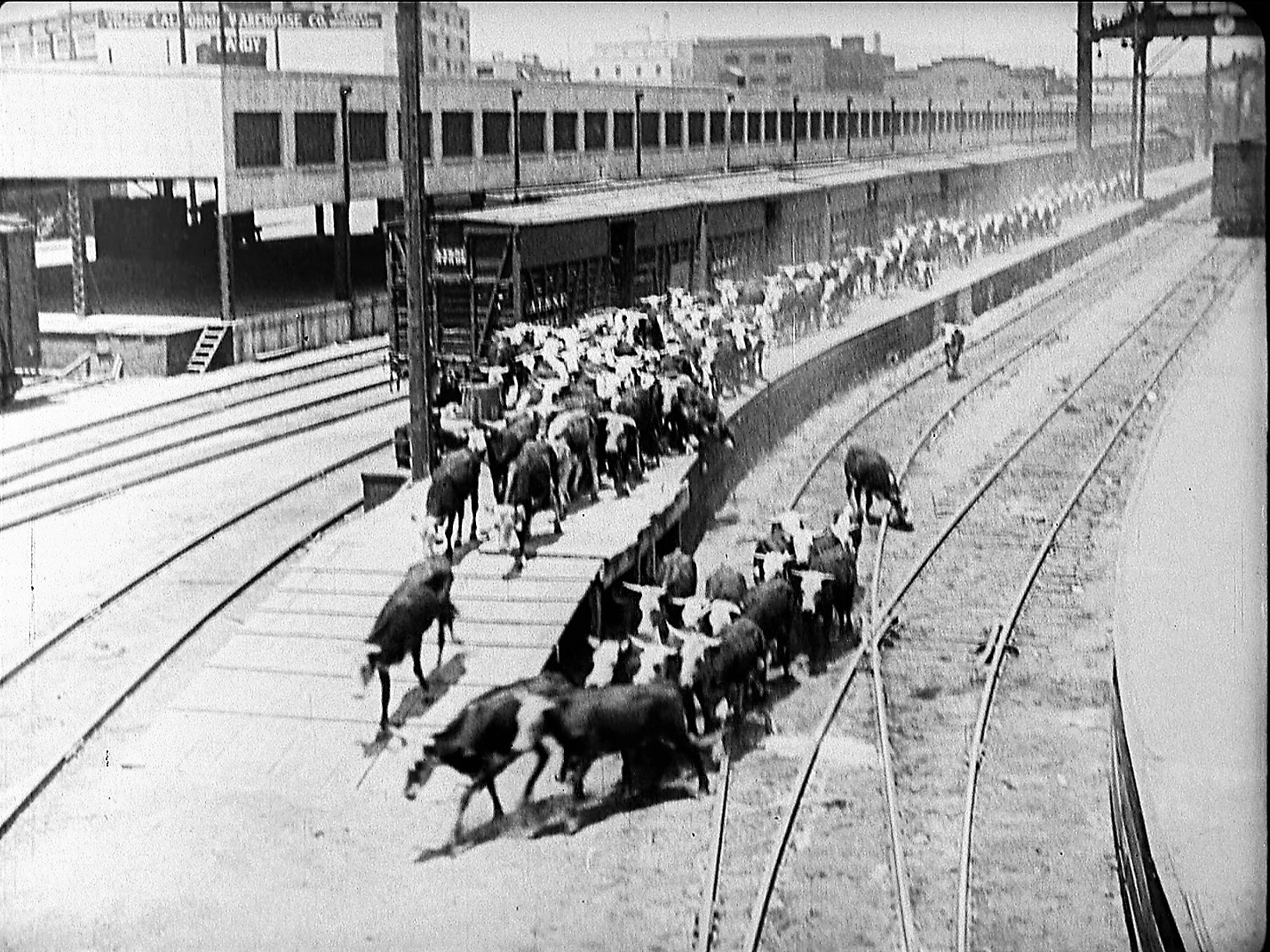

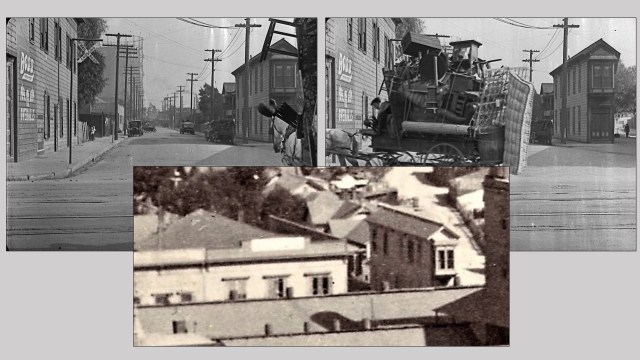

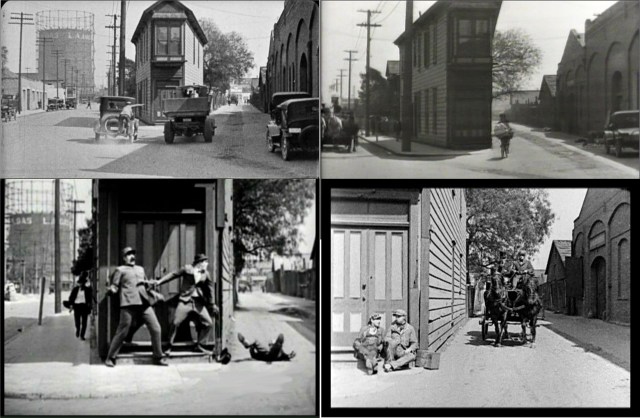

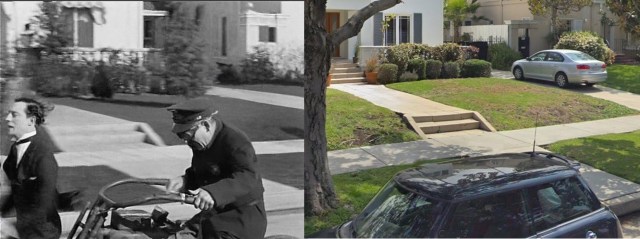

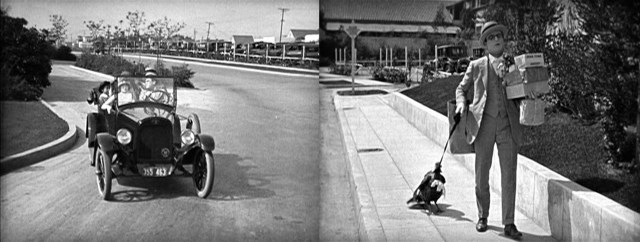

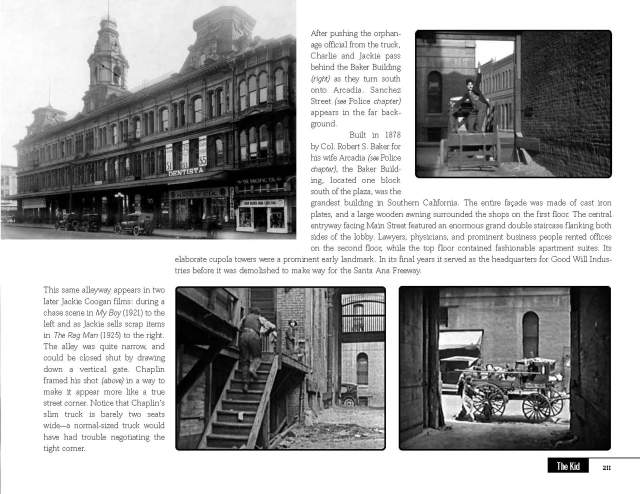

Running for their lives, Stan and Ollie turn the sharp corner from Culver Blvd. right (north) up Main Street in Culver City. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

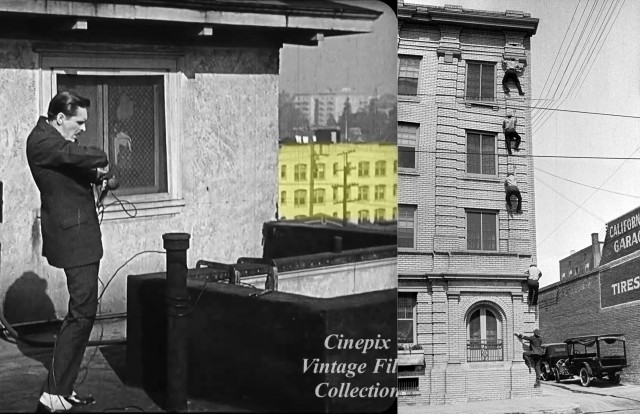

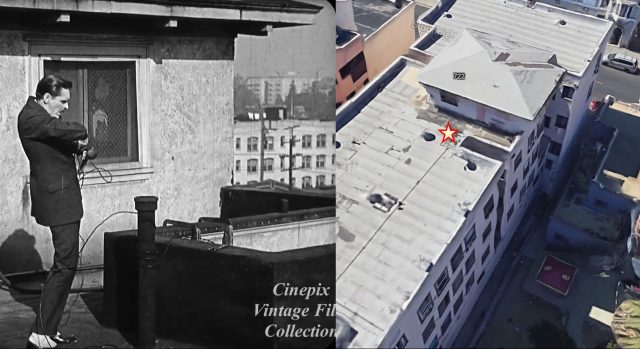

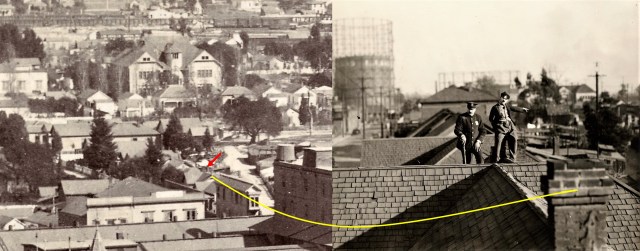

As they pedal away, behind them (yellow box) is the alley (now lost) where they would later unsuccessfully attempt to switch their mismatched pants during Liberty (1929). I document their rooftop antics in that film HERE. While the Culver Hotel remains in the modern view, lower right, the south side of Culver Blvd. across from the corner has been completely redeveloped. (C) 2020 Microsoft.

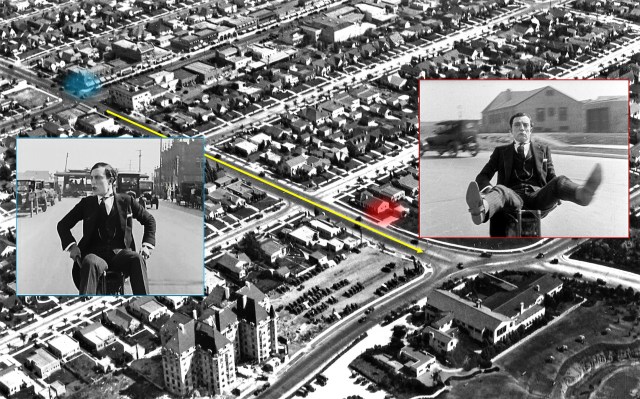

We now jump to downtown. Here they travel south down Grand from 6th Street.

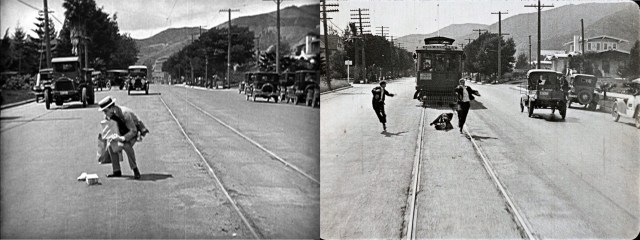

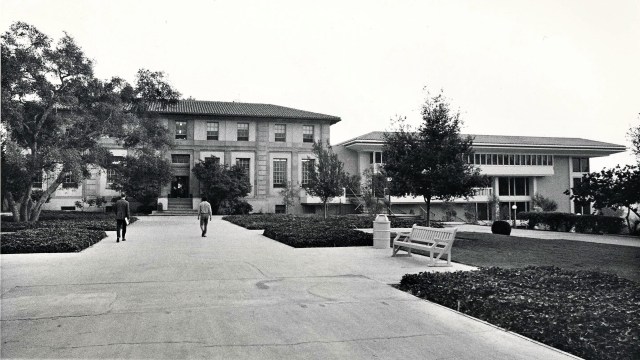

A point of view shot, left, speeding down Grand toward 5th, with a matching photo view LAPL. The large lawn on the right corner was part of the grounds for the LA Public Library, and is now the site of the library’s Mark Taper Auditorium.

Stan and Ollie race down Grand toward the former library lawn on the corner of 5th, past the former Biltmore Garage on the left, also seen in the 1934 Carole Lombard film Gay Bride upper right.

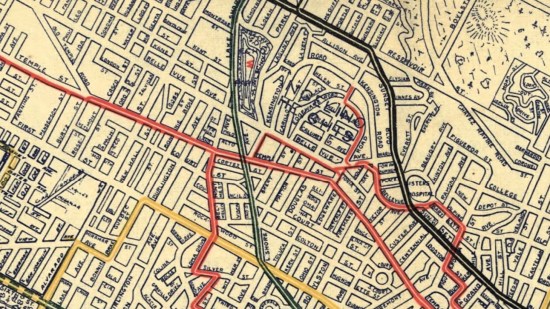

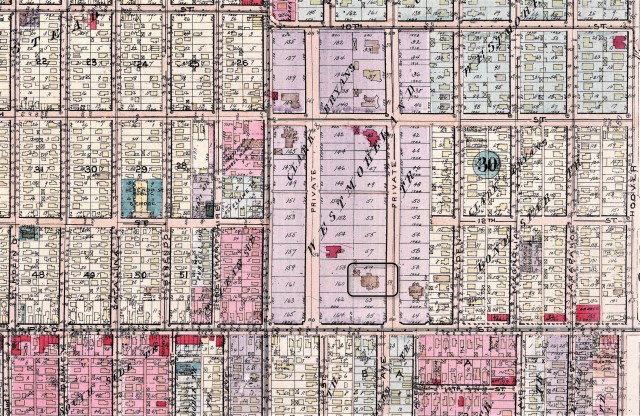

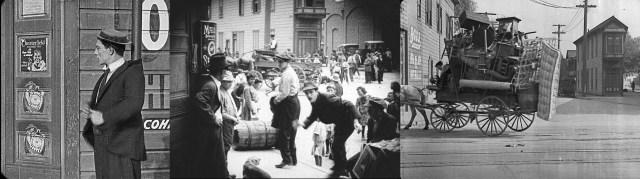

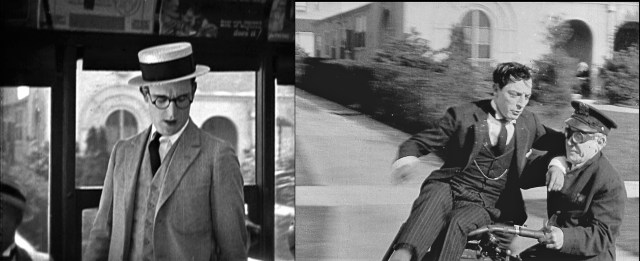

The bike odessy begins with Stan and Ollie crossing Grand Ave. west along 3rd Street, matching the arrow in this map designed by Piet Schreduers. Shown here, the section of 3rd Street on Bunker Hill above the 3rd Street Tunnel was just two blocks long, running from Angels Flight on Olive to Bunker Hill Ave.

Poor Oliver really pedaled Stan west uphill along 3rd from the corner of Grand. The matching color view comes from Marilyn Monroe’s 1956 movie Bus Stop during a scene intended to portray Phoenix Arizona! The Alta Vista Apartments, far left, appear again later below.

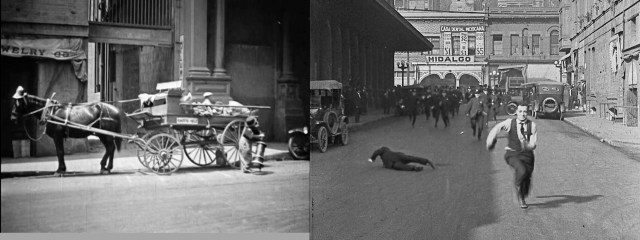

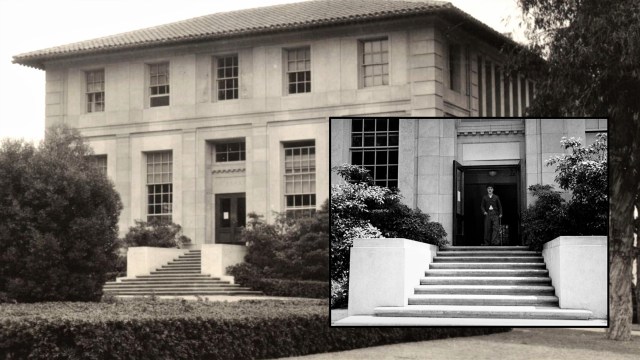

Click to enlarge – this panoramic view shows the backdrop as Stan and Ollie’s stunt doubles race south down Grand toward the corner of 5th. The far left frame comes from the movie, the other frames come from Africa F.O.B. (1922) starring Monty Banks, shown racing on foot down the street. Details mark the doorway to the former Sherwood Apartments at 431 S. Grand, and J. W. Johnson’s garage at 437 S. Grand. The pyramid peeking out in back

Click to enlarge – this panoramic view shows the backdrop as Stan and Ollie’s stunt doubles race south down Grand toward the corner of 5th. The far left frame comes from the movie, the other frames come from Africa F.O.B. (1922) starring Monty Banks, shown racing on foot down the street. Details mark the doorway to the former Sherwood Apartments at 431 S. Grand, and J. W. Johnson’s garage at 437 S. Grand. The pyramid peeking out in back  belonged to the former State Normal School (inset), torn down to accommodate the LA Public Library opening on that site in 1926. LAPL.

belonged to the former State Normal School (inset), torn down to accommodate the LA Public Library opening on that site in 1926. LAPL.

Thanks to Jim Dawson, the Sherwood Apartments portray San Francisco (look how steep the street is) during the opening scenes, at left, from Ida Lupino’s 1953 drama The Bigamist.

Opposite views of 3rd between Grand and Bunker Hill Ave., with Duck Soup looking west to the left, toward the corner blade sign for the Alta Vista Apartments (inset right), and Harold Lloyd’s race to the church in Girl Shy (1924) looking east to the right. Among Lloyd’s surviving films the corner of 3rd and Grand, depicted here, is where he filmed more often than any other spot in town. Most traffic along 3rd St passed through the tunnel beneath Bunker Hill. Only two blocks long, the short parallel section of 3rd St above the tunnel had little traffic and was easy to shut down for filming. California State Library. Novelist John Fante lived here briefly in 1933, immortalizing it (as the fictional Alta Loma) in his classic 1939 Bunker Hill novel Ask The Dust.

Opposite views of 3rd between Grand and Bunker Hill Ave., with Duck Soup looking west to the left, toward the corner blade sign for the Alta Vista Apartments (inset right), and Harold Lloyd’s race to the church in Girl Shy (1924) looking east to the right. Among Lloyd’s surviving films the corner of 3rd and Grand, depicted here, is where he filmed more often than any other spot in town. Most traffic along 3rd St passed through the tunnel beneath Bunker Hill. Only two blocks long, the short parallel section of 3rd St above the tunnel had little traffic and was easy to shut down for filming. California State Library. Novelist John Fante lived here briefly in 1933, immortalizing it (as the fictional Alta Loma) in his classic 1939 Bunker Hill novel Ask The Dust.

Above, Stan and Ollie travel south down Grand, with a garage at back, matched with stock footage of Bunker Hill used during a traveling car scene for the 1949 Columbia release Shockproof. The footage, available from the Internet Archive, was projected behind the actors sitting in a prop car filming inside a sound stage, creating the illusion they were driving outside. I have an extensive post documenting the numerous landmarks to appear in this Bunker Hill stock footage you can read HERE.

Further south, the lost Zelda Apartments (box) appears in both shots. The tall Sherwood Apartments, mentioned above, towers on the left behind Stan, while the edge of the Sherwood appears to the left of the 1949 frame.

The chase continues, matching views looking up Grand from 5th, with the library lawn to the left, and the former Biltmore Theater (Ben Hur sign) to the right.

A final view, tracing Stan and Ollie’s path along Grand, starting from the Sherwood Apartments to the left, then past the rooftop cars parked at Johnson’s garage to the right, then the Biltmore Garage across the street on the corner, and after crossing 5th, the Biltmore Theater on the other corner, all now lost, with the beautiful pyramid-capped LA Public Library in the foreground.

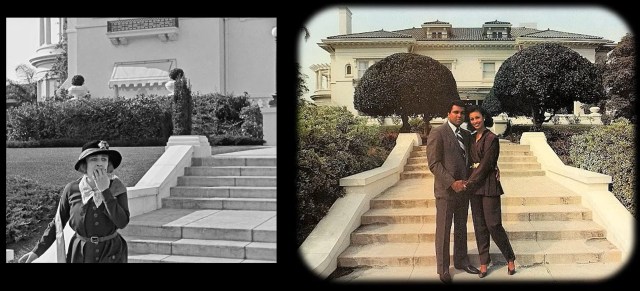

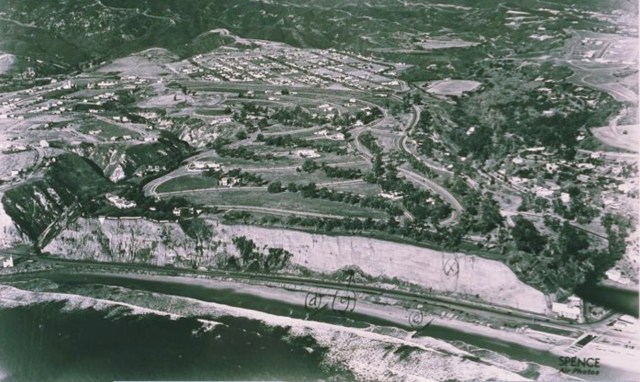

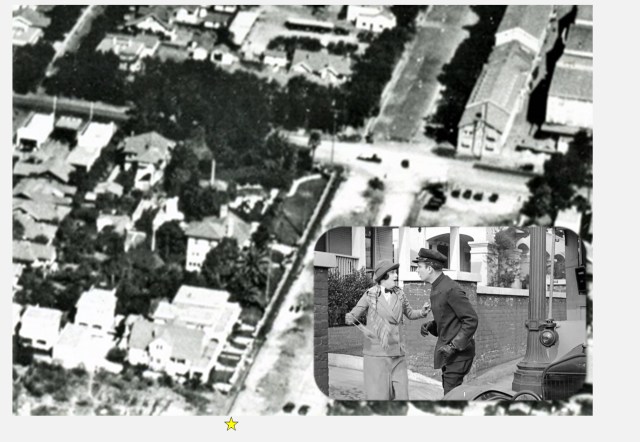

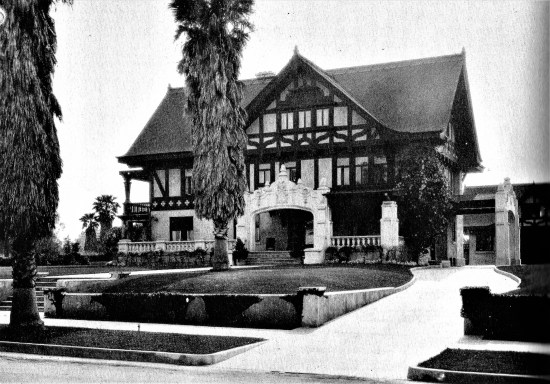

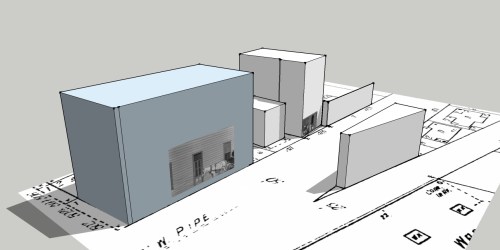

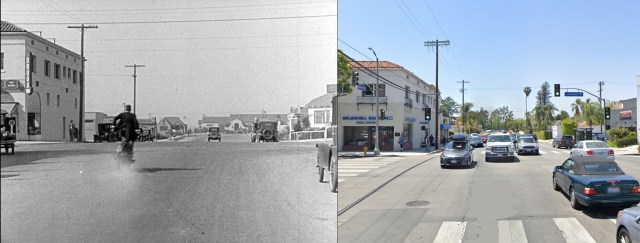

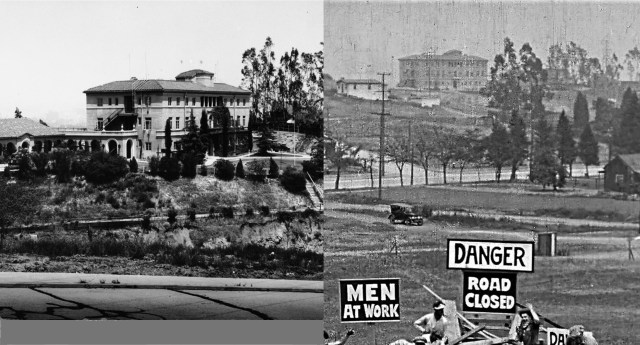

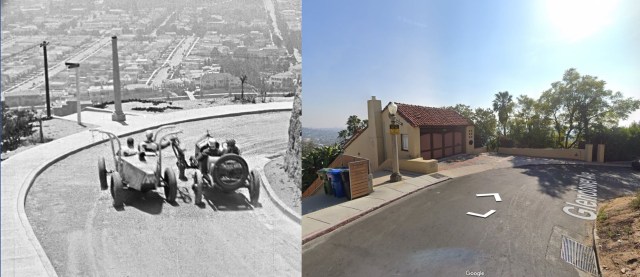

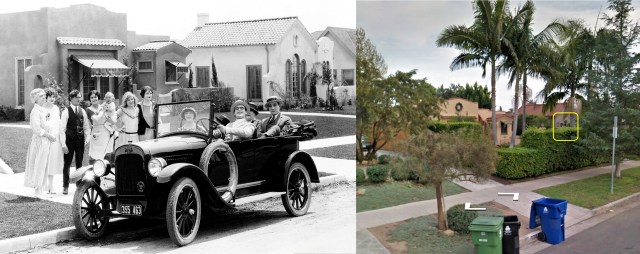

Leaving downtown behind, the Boys crash in front of 815 N. Alpine Drive in Beverly Hills, once standing on the SW corner of Sunset, and are soon pursued by the rangers. Flight c-4686, frame 24, UCSB Library.

This stately home also portrayed the governor’s mansion during Stan and Ollie’s The Second Hundred Years (1927). The lines and dimensions of the new home suggest the original home was first completely demolished. The neighboring home to the left in the movie frame appears to have since been remodeled.

Los Angeles residential historian Duncan Maginnis made this amazing discovery, and has identified many other homes appearing in classic silent films. He is the author of the amazingly rich and fascinating series of historical blog posts about classic Los Angeles neighborhoods, including BERKELEY SQUARE; WESTMORELAND PLACE; WILSHIRE BOULEVARD; ADAMS BOULEVARD; WINDSOR SQUARE; ST. JAMES PARK; and FREMONT PLACE.

The clue was the Max Whittier mansion looming tall in the background. Once standing on the NW corner of Sunset and Alpine, the Whittier home also no longer exists, but was notorious in the 1980s because a wealthy Saudi prince painted it gaudy colors, and lined the place with nude statues painted flesh color with highlighted genitals and pubic hair, creating quite a sight for tourists along Sunset Blvd. The inset image comes at 1:48 from a Youtube history video about Mr. Whittier. The image with the car above appears at 2:45, while the image upper left image above comes from the Alice Howell comedy Distilled Love (1920), in which Oliver Hardy plays a villain.

The clue was the Max Whittier mansion looming tall in the background. Once standing on the NW corner of Sunset and Alpine, the Whittier home also no longer exists, but was notorious in the 1980s because a wealthy Saudi prince painted it gaudy colors, and lined the place with nude statues painted flesh color with highlighted genitals and pubic hair, creating quite a sight for tourists along Sunset Blvd. The inset image comes at 1:48 from a Youtube history video about Mr. Whittier. The image with the car above appears at 2:45, while the image upper left image above comes from the Alice Howell comedy Distilled Love (1920), in which Oliver Hardy plays a villain.

Both views look north. Dressed as a maid, Stan loads stolen goods into a moving van, with the Whittier home looming in the background. The aerial view is from 1938.

A modern view shows both homes have been completely rebuilt. (C) 2020 Microsoft.

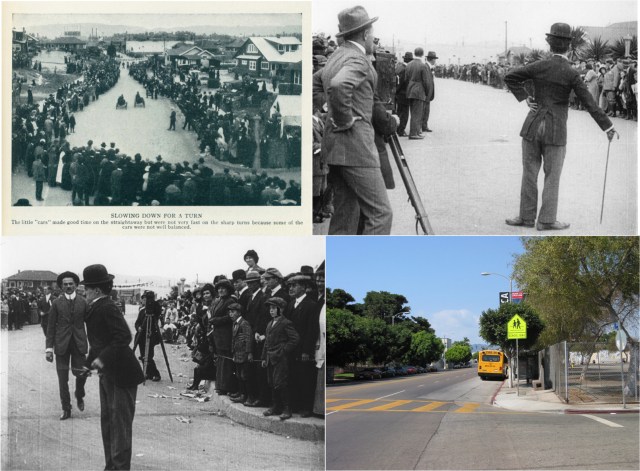

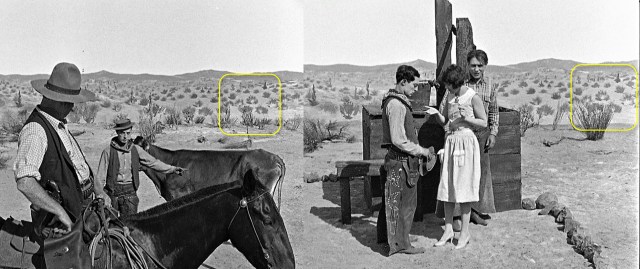

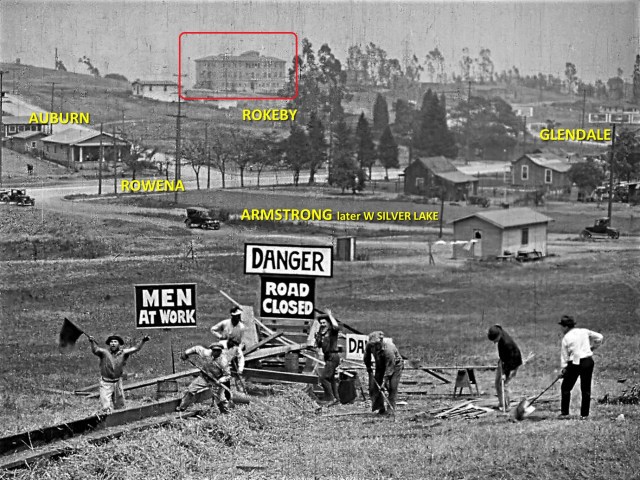

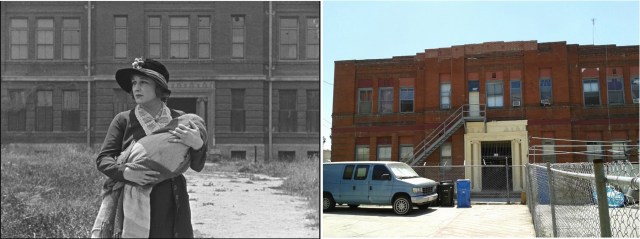

Captured by the rangers and forced to fight a fire, the movie ends with Stan and Ollie struggling with a loose and powerful fire hose on an open field beside Carson Street, a popular Roach filming site south of the studio. The central home behind them at 8885 Carson appears, for example, in the Charley Chase film All Wet (1927) upper right, and the silent Our Gang comedy The Fourth Alarm (1926) lower right.

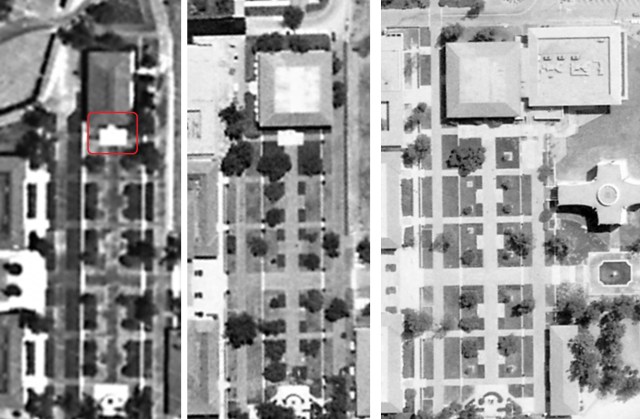

As first reported by Jim Dallape as part of the Back Lot Tour blog documenting scenes filmed around the Roach Studio, the final scene was staged in the open field to the south, with the home at 8885 Carson Street (yellow oval) marked in each image. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives; flight c-6926x, frame 36, UCSB Library.

Remarkably this home still stands. While the modern view shows the front facing Carson Street, the side of the home appearing in the film now abuts a cinder-block wall, blocking the view.

I want to express again my thanks to Duncan Maginnis, and my particular thanks to Dave Lord Heath, and his encyclopedic Hal Roach Studio films blog Another Nice Mess, for his insight and assistance with researching this post. Read Dave’s post about Duck Soup HERE.

This once lost movie was reconstructed with prints of the film preserved by the British Film Institute, a short scene preserved in the Library of Congress, and extra frames preserved in the Filmoteka Narodowa (FINA), as assembled and restored by the tireless efforts of Serge Bromberg, Eric Lange, and Lobster Films Laboratories.

Laurel & Hardy: Year One features all new restorations sourced from the best available materials contributed by archives and collectors around the world, as restored by Blackhawk Films® and Lobster Films in Paris. This comprehensive deluxe Blu-ray 2-Disc collection features thirteen extant films produced in 1927 and two additional films from before they were officially a team. First posted in April 2020, this Duck Soup blog has been updated with stunning new Blu-ray frame grabs from the film.

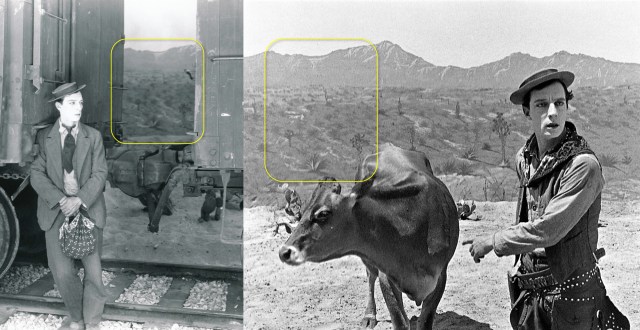

Please check out my latest YouTube video, revealing new visual discoveries about how Buster Keaton made The General, and the other dozen-plus videos on my YouTube Channel.

Where it all started, near the site of the hobo roundup at MacArthur Park.