Here’s the third and final post about W.C. Fields and Louise Brooks filming It’s The Old Army Game (1926) in Ocala, Florida. In the first post Fields plays an embattled pharmacist dealing with rude customers, nagging relatives, and pesky firefighters. Fields’ corner store still stands at the SW corner of Broadway and Main (now 1st). In the second post Fields’ employee Louise Brooks attracts an admirer, a smitten real estate promoter from New York played by William Gaxton, who follows Louise from the train station and around town. The plot gets underway here in the third post, when Fields allows Gaxton to sell real estate investments from his store. (In a reverse on the speculative 1920s Florida real estate boom, Gaxton sells New York property interests to people living in Florida!)

Here’s the third and final post about W.C. Fields and Louise Brooks filming It’s The Old Army Game (1926) in Ocala, Florida. In the first post Fields plays an embattled pharmacist dealing with rude customers, nagging relatives, and pesky firefighters. Fields’ corner store still stands at the SW corner of Broadway and Main (now 1st). In the second post Fields’ employee Louise Brooks attracts an admirer, a smitten real estate promoter from New York played by William Gaxton, who follows Louise from the train station and around town. The plot gets underway here in the third post, when Fields allows Gaxton to sell real estate investments from his store. (In a reverse on the speculative 1920s Florida real estate boom, Gaxton sells New York property interests to people living in Florida!)

Florida Photographic Collection

Above, inside the store, the property interests are selling like hotcakes. While these store scenes were filmed on an interior stage in Astoria, Queens, New York (where Fields later filmed Running Wild in 1927), the giant photo-mural in the background accurately represents the view you would have seen looking from the true corner drug store doorway – the large red brick Ocala House Hotel that once stood along the east (right) side of the town square, prominent in this vintage postcard looking north. Fields’ shop is the orange building to the lower right.

Above, inside the store, the property interests are selling like hotcakes. While these store scenes were filmed on an interior stage in Astoria, Queens, New York (where Fields later filmed Running Wild in 1927), the giant photo-mural in the background accurately represents the view you would have seen looking from the true corner drug store doorway – the large red brick Ocala House Hotel that once stood along the east (right) side of the town square, prominent in this vintage postcard looking north. Fields’ shop is the orange building to the lower right.

The giant photo-mural behind Fields upper left reveals the distinctive brick porch of the Ocala House, appearing earlier in the film in this true location shot above of Gaxton searching for Louise in the prior post. Later in the film Fields runs past this same porch, as described below. At left, you can read “OCALA HOUSE” on the photo-mural in this shot.

The giant photo-mural behind Fields upper left reveals the distinctive brick porch of the Ocala House, appearing earlier in the film in this true location shot above of Gaxton searching for Louise in the prior post. Later in the film Fields runs past this same porch, as described below. At left, you can read “OCALA HOUSE” on the photo-mural in this shot.

When Fields flees a mob later in the film, he runs north up Main (now 1st) towards Broadway, providing a more complete view of the Ocala House that stood east of the town square, matching this closer view of Gaxton searching for Louise from the prior post.

I’m fascinated by the Ocala House appearing on camera, because contemporary 1920s photos of this lost landmark are hard to find. (The above views are circa 1890 and 1950). When a devastating 1883 fire on Thanksgiving Day destroyed most wooden structures in town, the Ocala House Hotel was re-built with brick in 1884, serving as a local landmark for decades before being demolished in the 1960s. The hotel site today is an open lot.

I’m fascinated by the Ocala House appearing on camera, because contemporary 1920s photos of this lost landmark are hard to find. (The above views are circa 1890 and 1950). When a devastating 1883 fire on Thanksgiving Day destroyed most wooden structures in town, the Ocala House Hotel was re-built with brick in 1884, serving as a local landmark for decades before being demolished in the 1960s. The hotel site today is an open lot.

Cutting from the frenzied sales inside Fields’ store, we see a pair of New York police detectives planning Gaxton’s arrest for fraud. I cover this and all other New York scenes in the film in the next post.

Next, Fields takes a break from the real estate sales for a disastrous family picnic staged on the grounds of the Stotesbury estate, El Mirasol, in Palm Beach – detailed in this post.

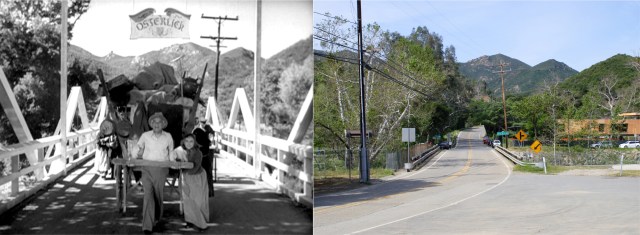

After discovering the real estate fraud, Fields heads to New York to try to set things right (see future post about New York). Unbeknownst to Fields, Gaxton, reformed by Louise Brooks’ love, comes through on the investment deals, and suddenly everyone in town has become wealthy. Above, Gaxton shares the good news beside the former Marion County Courthouse. At right, from the first post, the south end of the courthouse appears behind Gaxton earlier in the film as he stares into Fields’ corner shop window.

After discovering the real estate fraud, Fields heads to New York to try to set things right (see future post about New York). Unbeknownst to Fields, Gaxton, reformed by Louise Brooks’ love, comes through on the investment deals, and suddenly everyone in town has become wealthy. Above, Gaxton shares the good news beside the former Marion County Courthouse. At right, from the first post, the south end of the courthouse appears behind Gaxton earlier in the film as he stares into Fields’ corner shop window.

Views looking west towards the former courthouse. The bandstand in the postcard (or its replica) now stands in the center of the square.

Looking north – Fields’ route chased by the mob was limited to left-right along Broadway, Magnolia (orange) at left, and Main (now 1st) (pink). Osceola at right still has train tracks running north-south.

Returning from New York, seemingly a failure, Fields sneaks into town fearing a tar and feather mob reception. Instead, the ecstatic townspeople want to give Fields a hero’s welcome, resulting in their comedic chase around town.

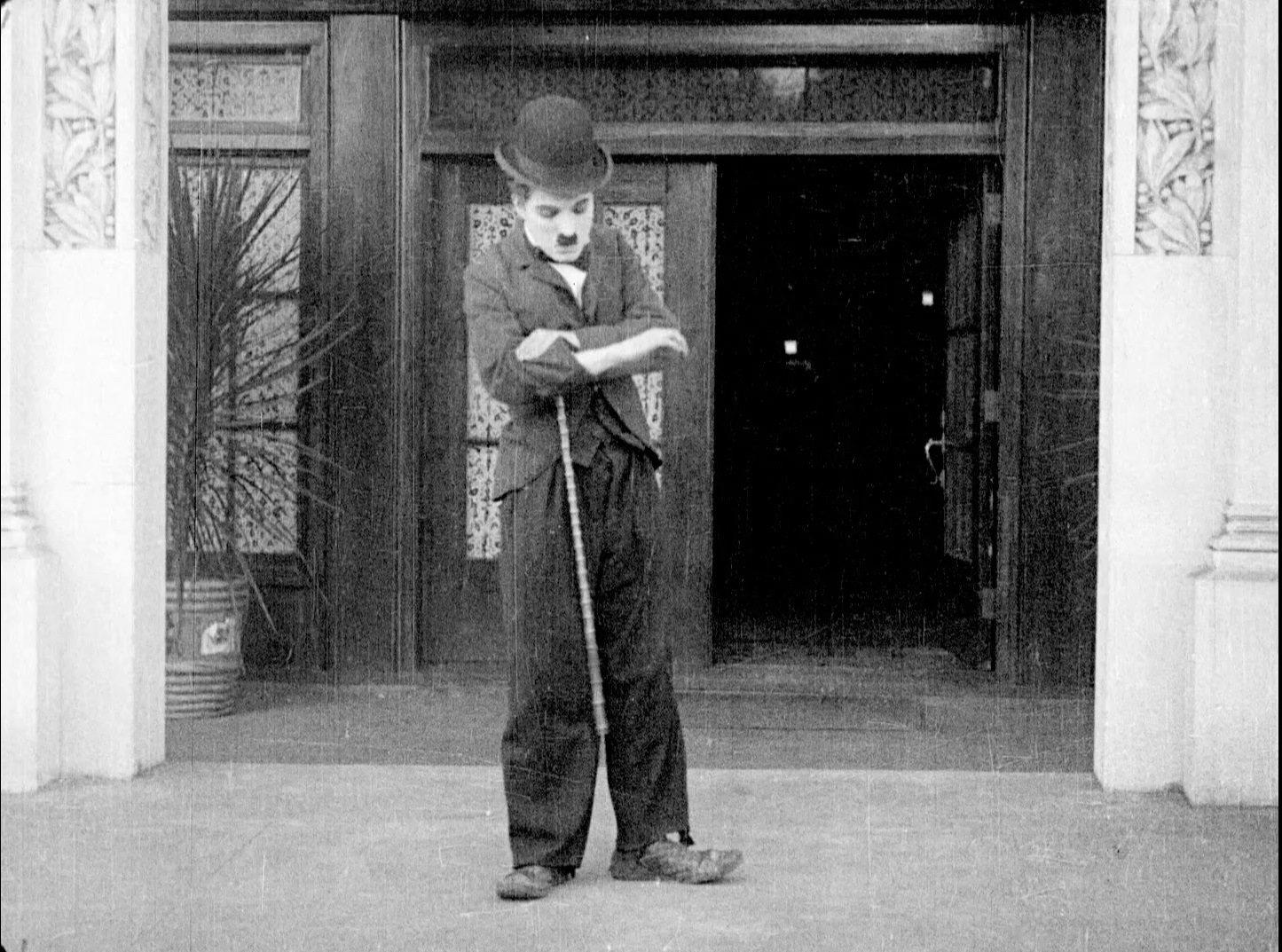

To begin the chase, Fields sprints east along Broadway from Main (now 1st) towards Osceola. His corner drug store appears at far back behind him, while closer at back is the same sidewalk scale Louise strolls by in the prior post.

Fields runs south down Main (now 1st) from Broadway, upper left view looks south, lower left looks north towards a magazine rack loaded with March and April 1926 publications, all discussed in this post. The vintage postcard looks north up Main (now 1st) from Fort King. Fields ran south towards us on the right – the red line points to the “EAT” sign discussed below. The postcard striped corner awning of the Harrington Hall hotel, see postcard above, also appears behind Louise, below. The left side buildings in the postcard remain standing – those to the right are all gone. [Update: Florida historian Lisa Bradberry writes that Fields, Brooks, director Sutherland, and the rest of the crew, stayed at Harrington Hall. Here are her two articles from 2005 about the filming W. C. Fields filming in Florida – 2005 articles by Lisa Bradberry.]

The prominent “EAT” sign appearing behind Fields and Louise is barely visible in the postcard above. Here, looking south, the view behind Fields shows the truncated store corner at the SW corner of Fort King – it appears to be the same building today.

Zooming in on this view north we see the two chimneys on the right (east) end of the former Ocala Post Office – the line of sight depicted at right. The postcard photo was taken after 1924, as the Sanborn fire insurance maps from that year show no buildings north of the square that would block the view of the Post Office from Fields’ spot.

At left, a crowd of elated townspeople joyfully recognize Fields passing by, and are eager to hail him a hero. Both views show the corner brick porch of the former Ocala House, once standing at the NE corner of Broadway and Main (now 1st).

Fields dashes west along Broadway towards Magnolia. The sidewalk awnings above Fields were not yet built in the earlier vintage photo. The yellow box marks the same south window on the E. W. Agnew & Co. building. This could be the same building with the red awning, now heavily remodeled, standing there today.

Again running west along Broadway from his corner store on Main (now 1st), only this time looking east, as Fields hopes to slip by unnoticed. The blue dot marks where Fields and Louise appeared near the sidewalk scale, mentioned previously. The men’s hat window display complements the reverse view of the matching window display appearing early in the film behind Elise Cavanna.

Again running west along Broadway from his corner store on Main (now 1st), only this time looking east, as Fields hopes to slip by unnoticed. The blue dot marks where Fields and Louise appeared near the sidewalk scale, mentioned previously. The men’s hat window display complements the reverse view of the matching window display appearing early in the film behind Elise Cavanna.

Florida Photographic Collection

By reversing these movie images, the combined window reflections provide a rare view of the south side of the Ocala House facing Broadway.

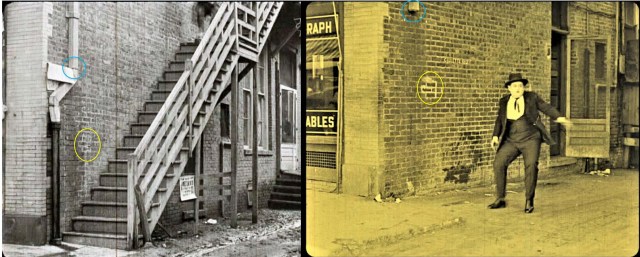

This combined image shows the NE corner of Broadway and Main (now 1st), and the site of the Western Union shop on the south side of the Ocala House appearing moments later in the film.

Fields races north up Main (now 1st) alongside his corner store on Broadway – the trees are part of the town square across from the Ocala House visible to the right.

Looking north up Magnolia at Broadway, Fields attempts sneaking past a security guard, with the Ocala National Bank building still standing behind him on the far NE corner of Magnolia and Silver Springs.

Looking north, a closer view of the bank visible behind Fields, along with matching corner masonry details visible in the vintage photo looking east down Broadway from Magnolia.

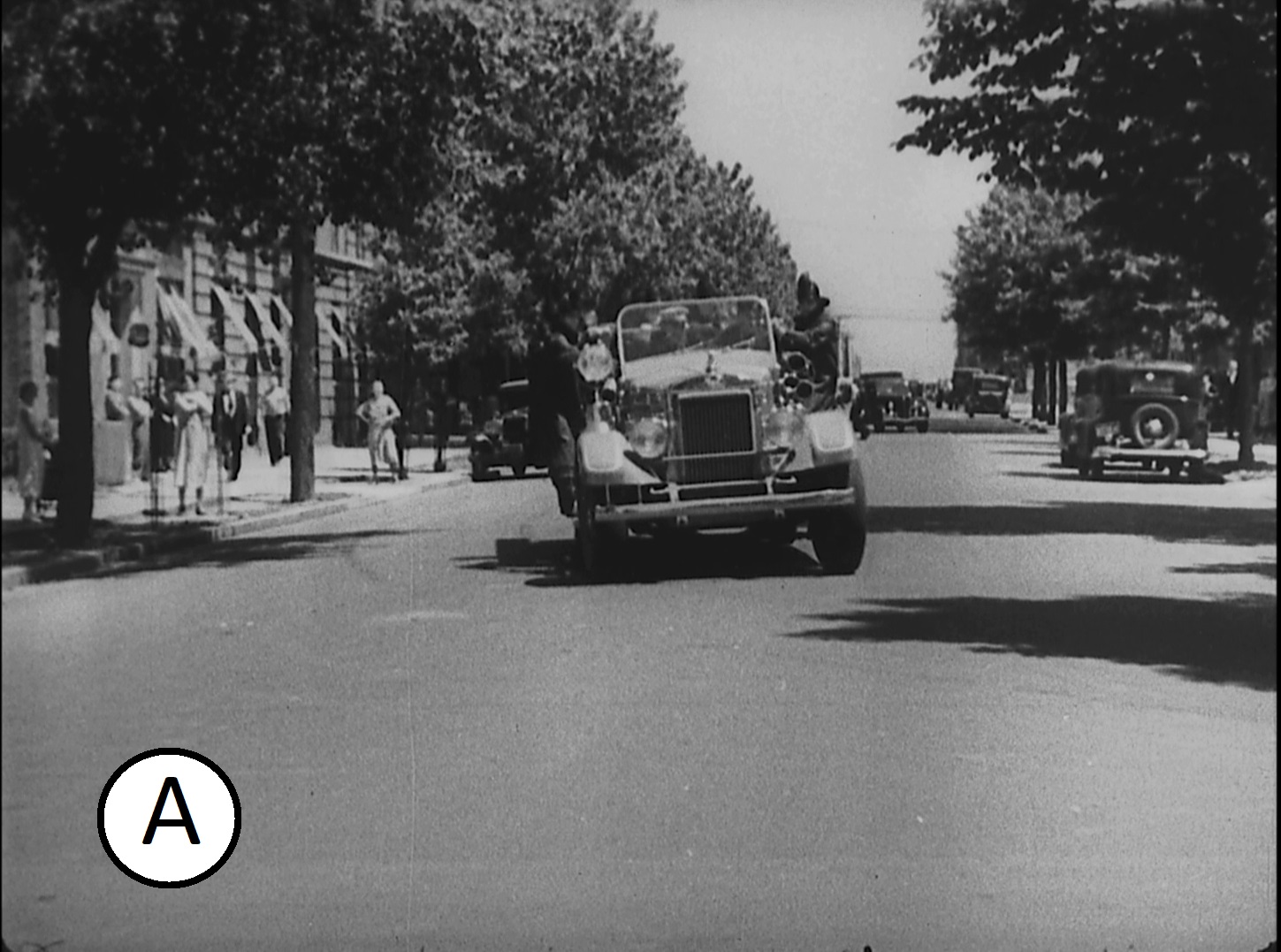

In the final tracking shot, Fields runs west towards the camera along Broadway from Osceola, as a huge crowd to the east masses downhill behind him. The view roughly matches the prior view of Louise at the same corner, with the train tracks running left-right along Osceola.

[Update: Ocala historian Evan Landrum provided this post card above showing the side of City Hall, matching the view with Louise. The fire station is around the corner to the right.]

Florida Photographic Collection

A bit further west, both the former Ocala bandstand (left), and prominent second floor porch of the former Hotel Hoffman (right), appear briefly behind Fields (see map above for details).

Even further west along Broadway, Fields runs past the Western Union shop (box) mentioned previously.

Florida Photographic Collection

Fields has now run west along Broadway from Osceola past the corner of Main (now 1st). Looking due east, the corner brick porch of the Ocala House Hotel appears to the left.

A later shot of the security guard struggling to keep up was also filmed looking east down Broadway from Osceola, the train tracks running left-right along Osceola are visible in the film, and still present today. The modern view now includes a train crossing sign.

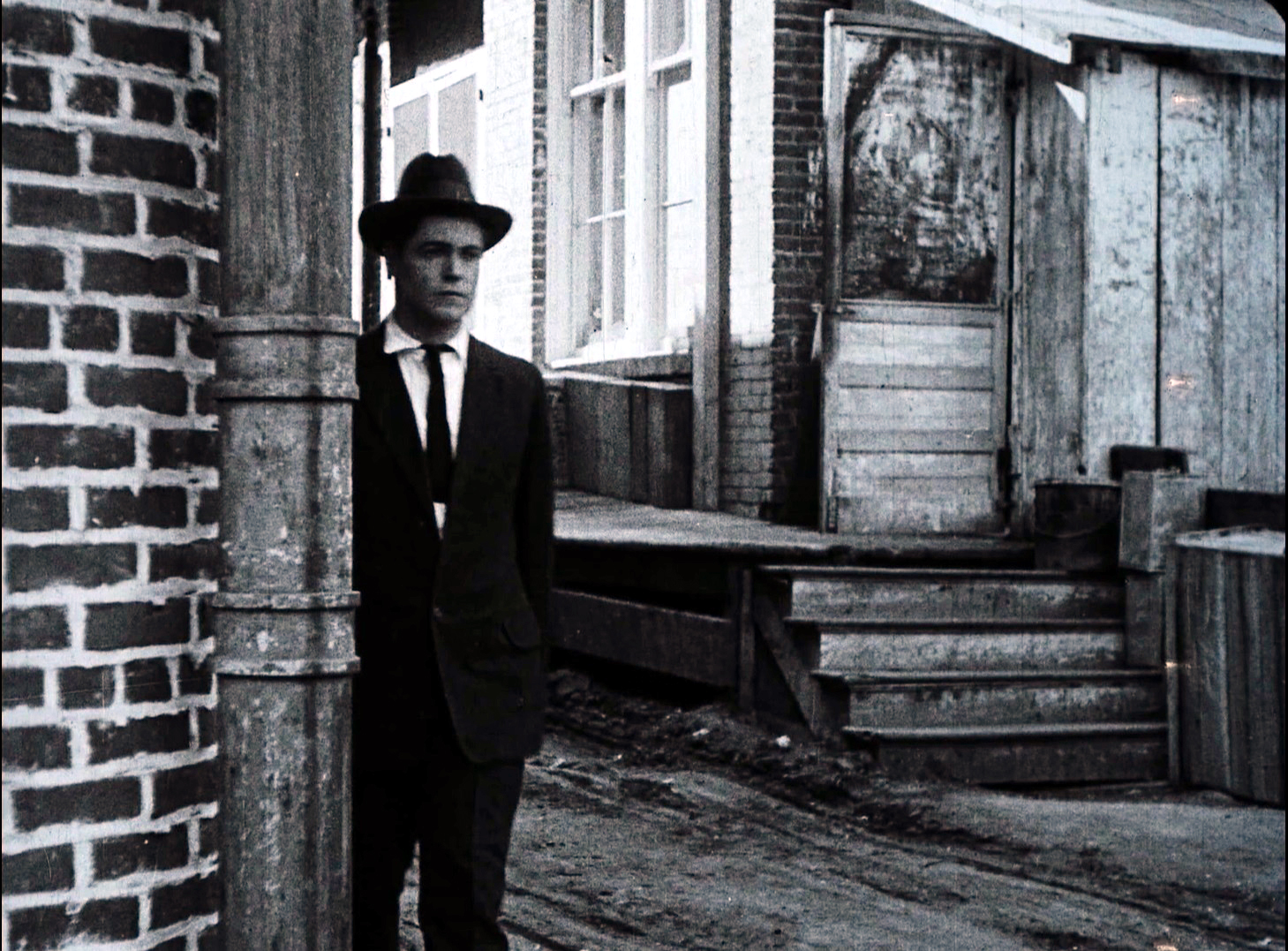

[Update: Above left, Fields dashes for safety hiding in the “county jail.” While I was unable to identify this spot, Ocala historian Evan Landrum supplied convincing evidence that the “jail” shot was staged at the back of a store at the SW corner of Main (now 1st Ave.) and Fort King. Notice the matching staggered rooftop firewall dividers (yellow boxes above). While too lengthy to list them all here, Evan noted many unique features in the movie frame that match exactly with details from his vintage color Sanborn map, including a sheet metal awning that extends almost to the corner of the building as depicted in the movie frame, and I am convinced he is correct.]

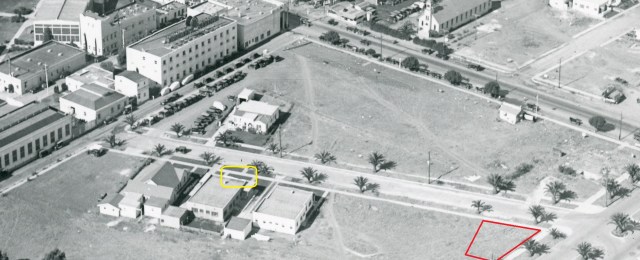

Above, the Sanborn maps, and a matching view of the “jail” building today. Consider too that nearly the entire film was shot within a block of Fields’ drug store at Broadway and Main, and this “jail” setting was also just a block away. The above aerial above and below is likely from the 1930s, and the metal awning appearing in the movie frame, and depicted on the map, has since been removed.

[Update: this aerial view supplied by Evan Landrum, looking SE, shows the corner of Broadway and Main (now 1st) (red box), where Fields’ drug store stands, and where many scenes were staged, and the jail scene setting a block further south (yellow box).]

All’s well that ends well; Fields is the home-town hero, we’re offered sage advice about swallowing birds in the hand, and true love triumphs. This delightful comedy is a wonderful precursor to Fields’ “talkie” career, and reminds us yet again of how vintage movies are also a vibrant historic record of the past.

Update: this formerly unsolved shot of the fire crew responding to Fields’ false fire alarm (see first post) was filmed looking east down Fort King towards the Fort King Apartments at the SW corner of Tuscawilla, built some time between the 1924 and 1930 editions of the Sanborn fire insurance maps.

Historic Ocala Preservation Society President Brian Stoothoff writes that the previously unidentified scene above of people from an arched porch running to greet Fields was likely filmed at the Ritz Historical Inn, 1205 E. Silver Springs Blvd., built in 1925, and now listed on the US National Register of Historic Places. The above images certainly look consistent. Moreover, given the Ritz was brand new in 1926, it’s easy to speculate Fields, Brooks, and the rest of the film crew might have stayed here during filming, as opposed to the Ocala House that appears in the film, that at the time was already several decades old.

[Update: I had pondered where the above shot of people exiting the bus was staged, and once again Ocala historian Evan Landrum supplied the answer. The view looks east along Broadway, with the trees beside City Hall at back, while to the right of the lamppost you can see a sign for the Marion Cafe that once stood at 118 Broadway.]

Both views above look east down Broadway. In the shot with the bus, the corner where Louise stood would be at back, on the right side of the street, and is blocked from view by the bus.

[Update: be sure to check out Florida historian Lisa Bradberry’s two articles from 2005 about the filming W. C. Fields filming in Florida – 2005 articles by Lisa Bradberry.]

Click to enlarge. [Update: Ocala historian Evan Landrum supplied this 1930s view looking SE, with the Fields drug store corner marked with a star across from the court house. Nearly every exterior scene in the film was staged somewhere within this amazing photo.]

Kino Lorber

It’s The Old Army Game.

Photo sources: The State Library and Archives of Florida, Marion County Historical Photographs.

Looking north at the Ocala National Bank building.

back of Mr. Hall’s home appearing in these three scenes above. Note: in Keaton’s view above the trees that belonged to the Jacob Stern estate are blocked from view by the Palmer Building on Cosmo nearing completion. At right, Keaton hides in a laundry basket beside Mr. Hall’s home during Neighbors. Notice the corner cast iron pole behind Buster which still remains. The home was demolished in 1956.

back of Mr. Hall’s home appearing in these three scenes above. Note: in Keaton’s view above the trees that belonged to the Jacob Stern estate are blocked from view by the Palmer Building on Cosmo nearing completion. At right, Keaton hides in a laundry basket beside Mr. Hall’s home during Neighbors. Notice the corner cast iron pole behind Buster which still remains. The home was demolished in 1956.