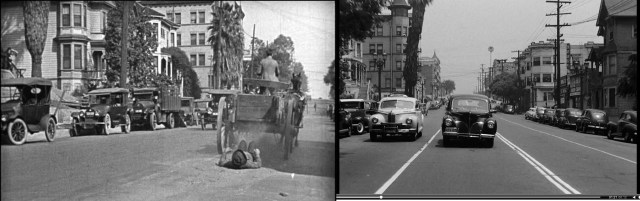

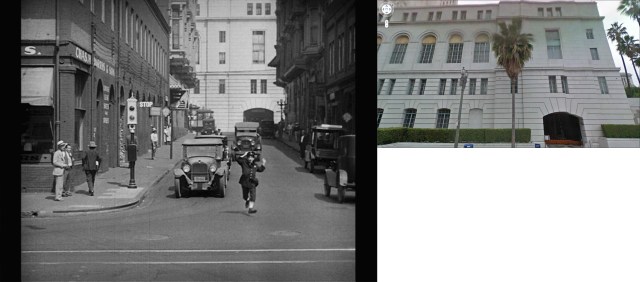

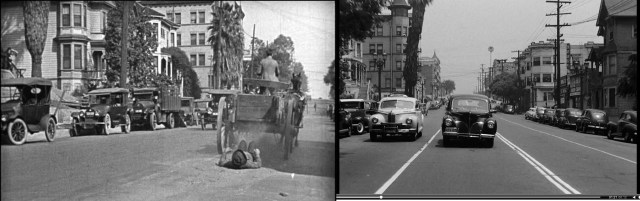

Click to enlarge. Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in Duck Soup (1927) and matching footage at 1:36

The Prelinger Archives has just posted some amazingly sharp movie footage of Bunker Hill and downtown Los Angeles taken in the late 1940s. The stock footage was intended to be projected behind actors filming a traveling car scene within an indoor studio, but apparently was never used. The footage not only provides a wonderful glimpse of post-WWII Bunker Hill, now lost to civic redevelopment, but illuminates Los Angeles during the silent film era as well. You can access the video here. [UPDATE – Jim Dawson reports that this footage appears briefly during Shockproof, the 1949 Columbia Pictures release, in a scene where Cornel Wilde picks up Patricia Knight at her place at 507 Second Street (the Koster house)]. [UPDATE – you can download a PowerPoint Presentation showing how Harold Lloyd filmed Girl Shy on Bunker Hill at this newer post].

The Prelinger Archives has just posted some amazingly sharp movie footage of Bunker Hill and downtown Los Angeles taken in the late 1940s. The stock footage was intended to be projected behind actors filming a traveling car scene within an indoor studio, but apparently was never used. The footage not only provides a wonderful glimpse of post-WWII Bunker Hill, now lost to civic redevelopment, but illuminates Los Angeles during the silent film era as well. You can access the video here. [UPDATE – Jim Dawson reports that this footage appears briefly during Shockproof, the 1949 Columbia Pictures release, in a scene where Cornel Wilde picks up Patricia Knight at her place at 507 Second Street (the Koster house)]. [UPDATE – you can download a PowerPoint Presentation showing how Harold Lloyd filmed Girl Shy on Bunker Hill at this newer post].

As I explain in my book Silent Visions, Harold Lloyd filmed scenes for seven different movies at the intersection of 3rd and Grand, on Bunker Hill, more scenes than at any other location in Los Angeles. As we will see, it was a popular place for Laurel and Hardy, and other Hal Roach Studio stars to film as well. The Prelinger film drives twice by Lloyd’s intersection of 3rd and Grand, providing razor sharp images of where Lloyd and other silent stars filmed.

Harold Lloyd’s An Eastern Westerner (1921) and frame 1:21

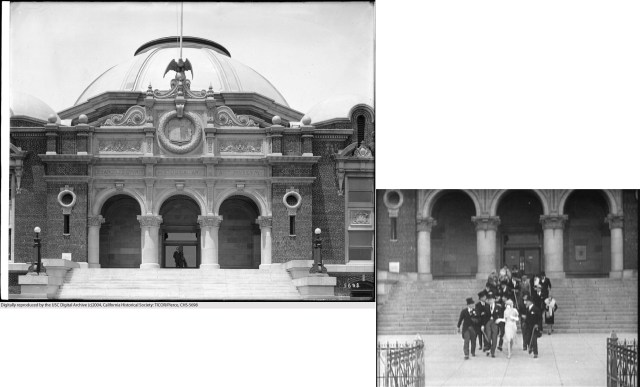

The corner of 3rd and Grand – the Angels Flight Pharmacy at the near corner, the Lovejoy Apartments at the far corner.

This brief scene from Harold Lloyd’s An Eastern Westerner (1921) (above) looks up Grand, past the Angels Flight Pharmacy on the near right corner of 3rd, and the Lovejoy Apartments on the far corner of 3rd, way back to the onion dome of the Winnewaska Apartments on the corner of 2nd and Grand. (oval, above).

The Non-Skid Kid (1922) and frame 1:08

The Winnewaska Apartment on the corner of 2nd and Grand

Ernie “Sunshine Sammy” Morrison appears in this scene from Hal Roach production The Non-Skid Kid (1922). Ernie is standing on Grand north of the 3rd Street intersection, and the onion dome of the Winnewaska Apartments on Second and Grand appears behind him up the street.

Captivated by the youth’s charm and mega-watt smile, Hal Roach signed Ernie to a two-year contract in 1919, before he had turned seven, making him reportedly the first black performer in history to be awarded a long-term Hollywood contract. Ernie appeared in three Lloyd pictures and numerous other Roach productions before becoming the first cast member of the original Our Gang.

Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy (1924) and frame 1:21

North up Grand towards 3rd.

Harold returned to 3rd and Grand to film several scenes for his first independently produced feature film Girl Shy (1924). Above, Harold is racing a commandeered horse wagon north up Grand towards 3rd.

Girl Shy and frame 2:47

The Lovejoy Apartments

Later in Girl Shy, Harold races his wagon west down 3rd towards the corner of Grand, past the Lovejoy Apartments. The same corner apartment building appears in the Prelinger film at 2:47 into the film.

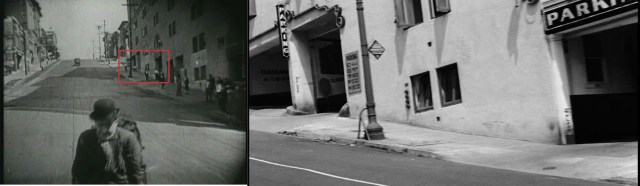

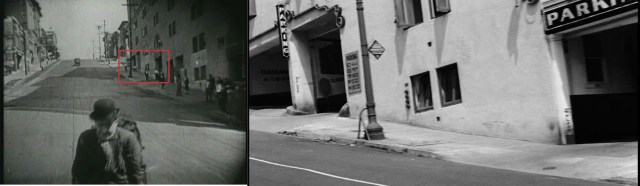

Harold Lloyd’s For Heaven’s Sake (1926) and frame 1:36. The fire escape of the Zelda Apartments (discussed below) appears to the left between the lamppost and the vertical garage sign.

During Harold Lloyd’s later feature comedy For Heaven’s Sake (1926), a double-decker bus commandeered by a quintet of drunken groomsmen races up Grand from the corner of 4th Street towards the 4th and Grand Service Garage, identified with a red oval on the sidewalk. In the Prelinger film, looking the opposite direction north up Grand, the garage appears to the left, also marked with a red oval.

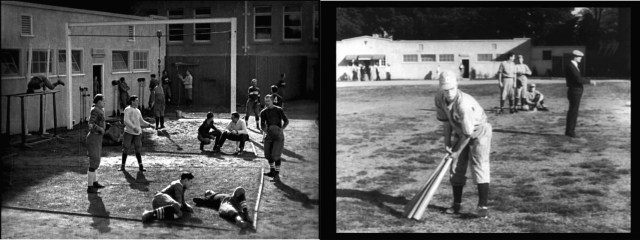

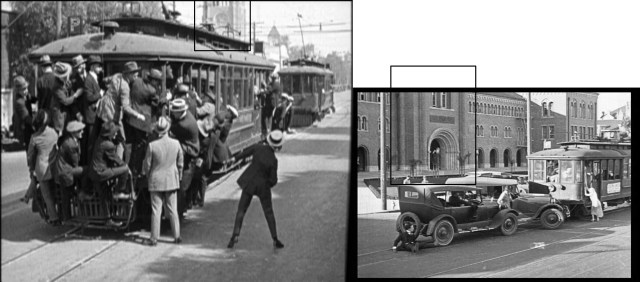

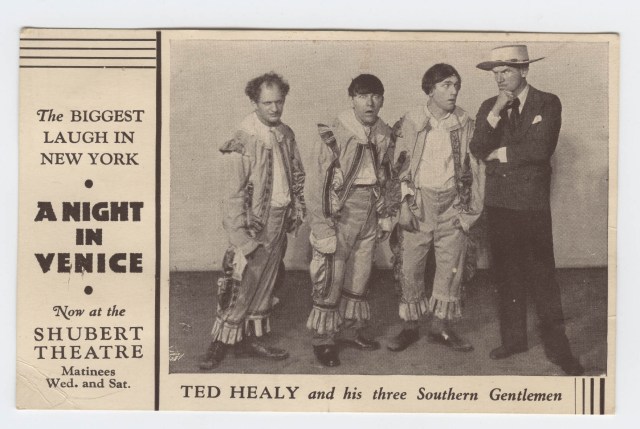

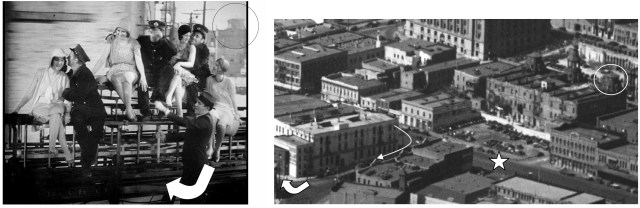

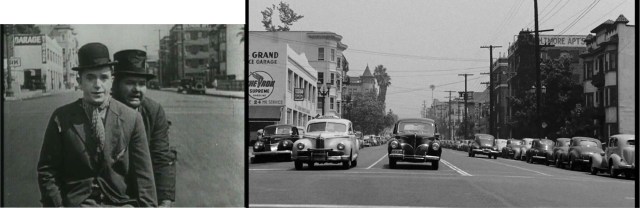

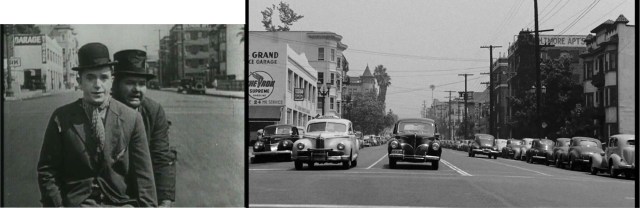

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in Duck Soup (1927) and frame 1:36

Although Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy had briefly appeared together years earlier in The Lucky Dog (cir. 1919), the short film Duck Soup (1927) marks the first time the two comedic actors worked together at the Hal Roach Studios, though not yet paired as a “team.” During the film Oliver gives Stan a ride on his bicycle, including several scenes of them traveling south down Grand Avenue. During these scenes the camera either points north up Grand, so that we can see the actors, or down Grand, providing the audience with a point of view shot of the duo’s downhill ride. Above, Stan and Ollie ride south down Grand past the corner of 4th, with the 4th and Grand Service Garage visible behind them to the left.

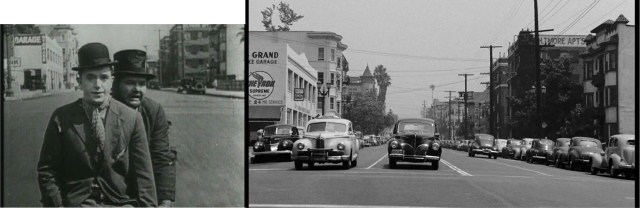

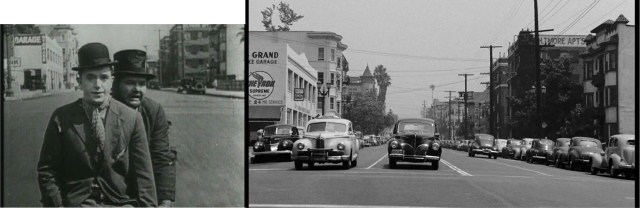

Duck Soup and frame 2:00 showing the Zelda Apartments on the SW corner of 4th and Grand.

A bit further during Stan and Ollie’s ride down Grand from 4th Street, we can see the Zelda Apartments (red oval) in both the movie, and at frame 2:00 during the Prelinger film.

Duck Soup and frame 3:32, showing the Biltmore Garage.

As Stan and Ollie continue down Grand from 4th, they pass by the Biltmore Garage on the SE corner of 5th and Grand. The red box above matches the doors and windows in the Prelinger frame.

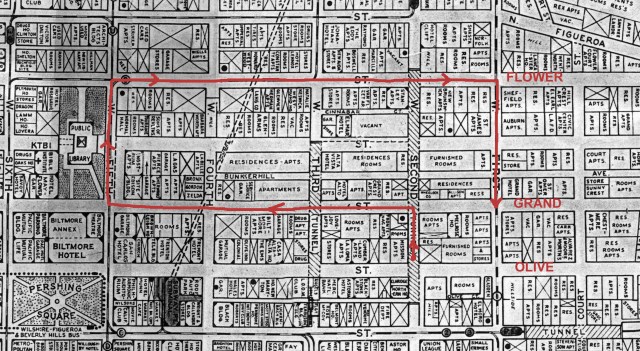

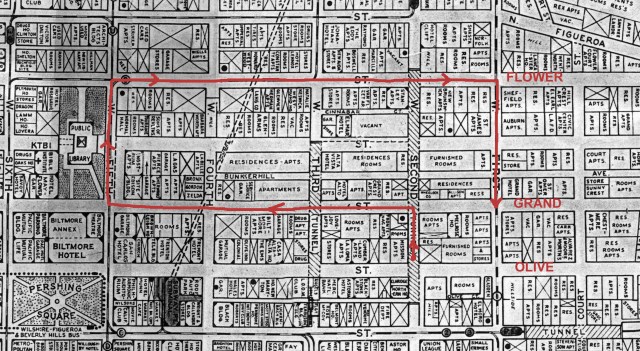

The Prelinger film continues south down Grand, turning right (west) at 5th, past the Biltmore Theater, the Biltmore Hotel, and the Los Angeles Public Library, then turning right (north) at Flower, and continuing north to 1st Street, where it turns right (east) onto 1st Street, where the film ends. [Note: some blogs regarding the Prelinger film incorrectly state that the last turn of the film is onto 2nd Street, forgetting that the drop-off of the west end of the 2nd Street tunnel would appear in the background during the turn if this was correct.]

Route in Prelinger Bunker Hill Stock Footage

Stock footage – The Internet Archive – Rick Prelinger, Prelinger Archives.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California; Security Pacific National Bank Photograph Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

The Prelinger Archives has just posted some amazingly sharp movie footage of Bunker Hill and downtown Los Angeles taken in the late 1940s. The stock footage was intended to be projected behind actors filming a traveling car scene within an indoor studio, but apparently was never used. The footage not only provides a wonderful glimpse of post-WWII Bunker Hill, now lost to civic redevelopment, but illuminates Los Angeles during the silent film era as well.

The Prelinger Archives has just posted some amazingly sharp movie footage of Bunker Hill and downtown Los Angeles taken in the late 1940s. The stock footage was intended to be projected behind actors filming a traveling car scene within an indoor studio, but apparently was never used. The footage not only provides a wonderful glimpse of post-WWII Bunker Hill, now lost to civic redevelopment, but illuminates Los Angeles during the silent film era as well.