Laurel and Hardy in The Second Hundred Years (1927) – behind them, the extant six story Los Angeles County Hospital services building. (C) 2012 Microsoft Corporation

Jails and silent comedies! A match made in heaven. This post shows where (ONE) Laurel and Hardy filmed the jailbreak scene from The Second Hundred Years, (TWO) Charlie Chaplin filmed a prison release scene in Police, (THREE) Laurel and Hardy filmed being sent to prison in The Hoose-Gow, and (FOUR) Harold Lloyd and Laurel and Hardy filmed beside the Lincoln Heights Jail.

ONE – Laurel and Hardy at the LACH south gate

An elevated bridge, or causeway, still standing, connects the services building to facilities on the other side of a shallow ravine. (C) 2012 Microsoft Corporation. Pictometry

Click to enlarge. March 9, 1913 – Los Angeles Times

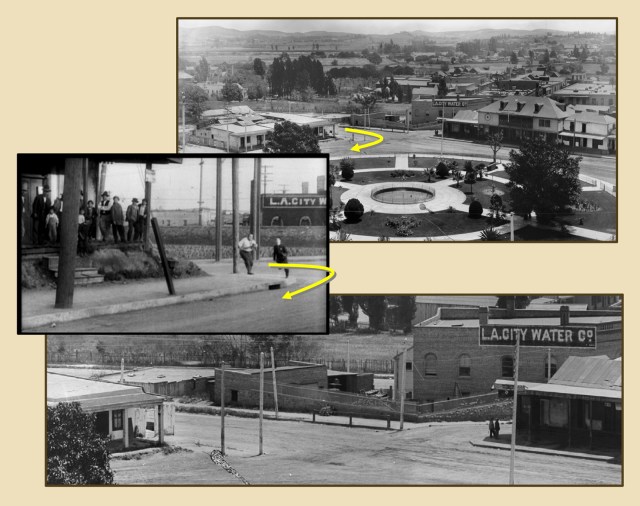

The above scenes from The Second Hundred Years were filmed at the south entrance gate to the former campus of the Los Angeles County Hospital, located at approximately 1651 Marengo Street.* Construction for the campus began in 1913, initially comprised of nineteen fireproof buildings standing on fifteen acres bounded by Mission Road and Marengo Street, Griffith Avenue (now Zonal Avenue), and Wood Avenue (now lost). As shown above, and at the end of this post, part of the south gate at what was once Wood Avenue still remains standing. An ornamental fence of reinforced concrete and iron construction surrounded the grounds, and visitors and employees were required to pass through a gate lodge to ensure no one would enter the grounds without authorization. The fence was one of the first innovations urged by superintendent Dr. C. H. Whitman when he took charge of the facility in 1909. This jail-like fence caught the attention of early film-makers, as it appears in each of the films discussed here.

*I do not know whom to acknowledge in the Laurel and Hardy fan community for this original discovery, but will gladly credit them if someone will identify him or her to me.

The box marks the south gate entrance employed by Laurel and Hardy (above), the oval marks the north gate beside the Psychopathic Hospital used by Charlie Chaplin, and others, (below). Baist’s Real Estate Surveys of Los Angeles 1914 – Plate 026. HistoricMapWorks.com

TWO – Charlie Chaplin at the LACH north gate

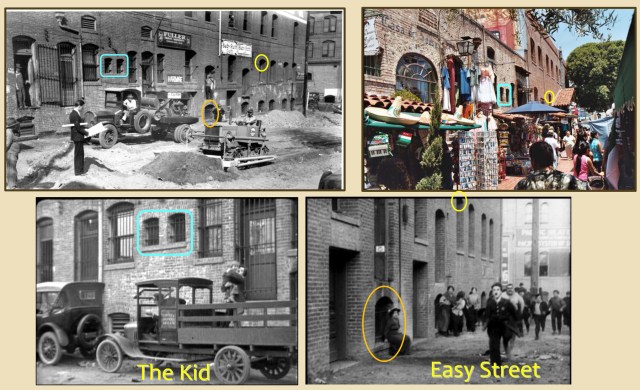

The north gate – Hank Mann in The Janitor (1919); Charlie Chaplin in Police (1916); Stan Laurel in Detained (1924).

While Laurel and Hardy used the Los Angeles County Hospital campus south gate to film The Second Hundred Years, the above frames show that comedians Hank Mann, Charlie Chaplin, and then-solo act Stan Laurel all filmed at the north gate to the campus, as shown below, beside the Los Angeles County Psychopathic Hospital that opened on August 3, 1914. With soft, cream-shaded walls, and accommodations for 100, the facility applied the latest scientific methods to treat patients suffering from drug and drink habits, and those afflicted with sudden manias. Referrals to the asylum were handled by the Lunacy Commission, which handled an average of 130 insane persons a month. The Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, and the Los Angeles Times drawing above, show that a small Leper Ward stood south of the Psychopathic Hospital.

As mentioned in my prior post, I did not know where this Chaplin setting was located until Mary Mallory, author of Hollywoodland, and who blogs regularly about classic Los Angeles and Hollywood at ladailymirror.com, suggested it might be in the neighborhood of the Laurel and Hardy gate. Further research showed Mary was absolutely right.

Click to enlarge. Looking south at the Psychopathic Ward of the Los Angeles County Hospital building, on Griffin (now Zonal Avenue). The yellow ovals identify the same matching side entrance lamps. Security Pacific National Bank Photograph Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

A larger comparison view of the Psychopathic Hospital and Charlie beside the north entrance gate. The yellow ovals mark the same side entrance lamps.

Photos of the Psychopathic Hospital, and several other of the original nineteen brick buildings that comprised the original Los Angeles County Hospital campus, are available for view by searching online at the LA Public Library, and the USC Digital Archive. One such photo below shows the relation of the Psychopathic Hospital to the then-newly opened Los Angeles County – University of Southern California Medical Center complex, situated on an adjacent fifty-six acre hilltop parcel. Silent film star Mary Pickford helped lay the cornerstone for the center on December 7, 1930. The LAC-USC Medical Center remains one of the largest public hospitals in the country.

Click to enlarge. The arrow shows the point of view of Chaplin’s camera towards the Psychopathic Hospital. The oval encompasses the twin side entrance lamps highlighted above. Security Pacific National Bank Photograph Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

THREE – Laurel and Hardy return to the LACH south gate

Laurel and Hardy returned to the Los Angeles County Hospital south gate entrance two years later to film the opening scenes from The Hoose-Gow. The view below shows a paddy wagon traveling south down Marengo Street, from Mission Road, towards the south gate.

Traveling down Marengo Street in The Hoose-Gow (1929).

Annotated on the images above and below are (1) the Tuberculosis Ward built in 1912, (2) the Jail Ward (there was an actual jail on the campus!), (3) the Isolation Ward, and (4), above, the Services Building. The green arrow in each image points down Marengo Street, the red box in each image marks the spot of the south gate.

Click to enlarge. Security Pacific National Bank Photograph Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

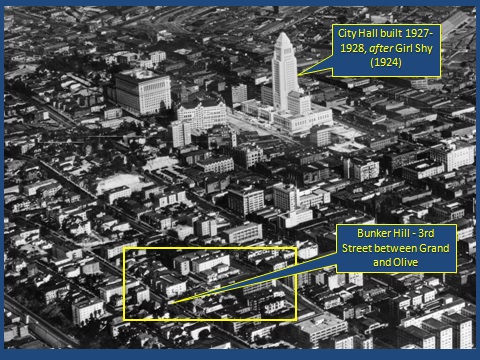

To put the pieces all into perspective, the aerial view below shows the different filming sites, dwarfed by the massive LAC-USC Medical Center, and where Harold Lloyd filmed a failed suicide attempt nearby in the deceptively shallow waters of Eastlake Park (now Lincoln Park) for a scene from his short comedy Haunted Spooks.

Click to enlarge. N. Mission Road runs along the left side. Upper left, Harold Lloyd in Haunted Spooks (1920), the yellow box marks the extant Eastlake Park (now Lincoln Park) boathouse; upper center Charlie Chaplin beside the campus north gate on Zonal Avenue; upper right, Laurel and Hardy beside the campus south gate on Marengo Street. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

FOUR – Laurel and Hardy, and Harold Lloyd, at the Lincoln Heights Jail

At the left, Harold Lloyd in Take A Chance (1918), to the right, Stan and Ollie from The Hoose-Gow. Notice the matching address, man hole, and water spigot.

Take A Chance

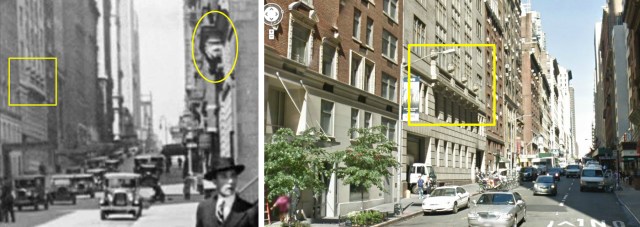

Lastly, during the opening of The Hoose-Gow, immediately after the paddy wagon above enters the campus south gate, the action cuts to a shot of the wagon unloading in front of the former Los Angeles East Side Division city jail, at 419 N. Avenue 19, the same jail setting appearing in Harold Lloyd’s 1918 short comedy Take A Chance. Lloyd’s producer at the time, Hal Roach, obviously remembered this jail setting, and used it again a decade later for the Laurel and Hardy short. The jail was located a few blocks north of the hospital campus, just east of the Los Angeles River.

Shuttered Lincoln Heights Jail – (C) 2012 Google

I was able to identify the site because another jail scene from Take A Chance (inset above) shows the former West American Rubber Co., at 400 N. Avenue 19, across the street from the 419 address jail. The jail was originally built in 1909, and expanded, as shown in The Hoose-Gow, in 1913. The jail was re-built again in 1931 to the five-story structure still standing there today (inset right), and later closed in 1965. Known as the Lincoln Heights Jail, the facility became infamous for Bloody Christmas, the vicious beating of Latino prisoners at the hands of the police, that took place on December 25, 1951, and portrayed in the James Ellroy novel and 1997 movie L.A. Confidential.

Today nearly all of the original Los Angeles County Hospital campus buildings have been demolished. One holdout pictured below, 1104 N. Mission Road, originally the LACH Administration Building, is now used as headquarters for the Los Angeles County Coroner’s office. The original brick gate lodge, to the left of the entrance road shown below (No. 15 on the above Los Angeles Times map) also still stands.

1104 N. Mission Road – now the Coroner’s Office. Security Pacific National Bank Photograph Collection/Los Angeles Public Library. (C) 2012 Google

You can find The Janitor on the Silent Comedy Mafia #1 DVD; Police can be found on the Chaplin Essanay Comedies Vol. 3 DVD; and Detained can be found on the Stan Laurel Collection Volume 2 DVD. The Second Hundred Years, Hal Roach Studios, Inc.; (C) 2000 Richard Feiner and Company, Inc. and Hal Roach Studios [Trust]. The Hoose-Gow (B&W) (C) 1929 Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer; (C) Hal Roach Studios, Inc. ; (C) 2011 RHI Entertainment Distribution, LLC.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Below, a Google Street View of the remaining half of the south gate.

You can get a sense of how bare suburban development was here in the early 1940s by comparing these images above from the two movies. Each image shows the north face of the bungalow that once stood at 335 Screenland Drive – at the time the only home on the block. Today large apartment blocks squat along both sides of Screenland Drive. The map at the left looks south, and shows the point of view from the Stooges’ movie (left arrow) and from Buster’s movie (right arrow) towards the home at 335 Screenland. Only four homes (and three detached garages) stood on the bare land south of the Columbia Ranch during the time of filming.

You can get a sense of how bare suburban development was here in the early 1940s by comparing these images above from the two movies. Each image shows the north face of the bungalow that once stood at 335 Screenland Drive – at the time the only home on the block. Today large apartment blocks squat along both sides of Screenland Drive. The map at the left looks south, and shows the point of view from the Stooges’ movie (left arrow) and from Buster’s movie (right arrow) towards the home at 335 Screenland. Only four homes (and three detached garages) stood on the bare land south of the Columbia Ranch during the time of filming.