The San Francisco Silent Film Festival 2018 schedule has just been announced! One highlight is the Thursday, May 31 world premiere restoration of Universal’s 1925 Harry Carey action/drama Soft Shoes, in which Carey (right) seeks to rescue a young woman from a life of crime. Purportedly set in San Francisco,

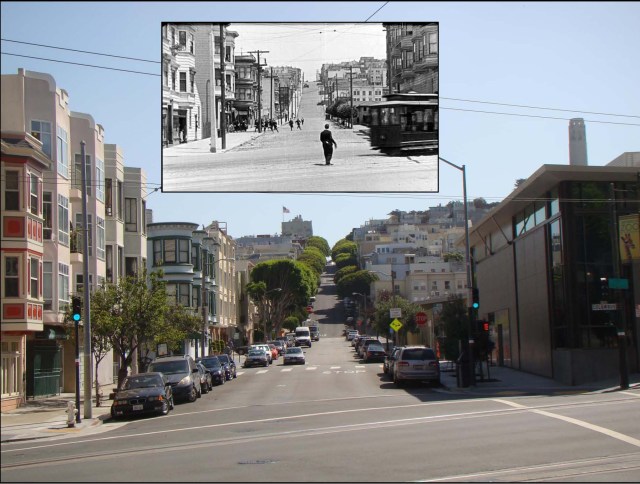

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival 2018 schedule has just been announced! One highlight is the Thursday, May 31 world premiere restoration of Universal’s 1925 Harry Carey action/drama Soft Shoes, in which Carey (right) seeks to rescue a young woman from a life of crime. Purportedly set in San Francisco,  the film’s many exteriors were all filmed, unsurprisingly, in Los Angeles instead. But as shown below, the movie intersects remarkably with classic films made by Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Stan Laurel, while documenting historic LA settings, including its long lost Chinatown. This brief shot at left, looking west towards the Ferry Building, is the lone scene filmed in San Francisco.

the film’s many exteriors were all filmed, unsurprisingly, in Los Angeles instead. But as shown below, the movie intersects remarkably with classic films made by Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Stan Laurel, while documenting historic LA settings, including its long lost Chinatown. This brief shot at left, looking west towards the Ferry Building, is the lone scene filmed in San Francisco.

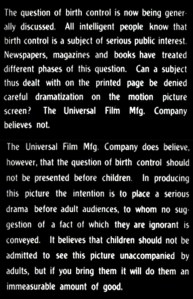

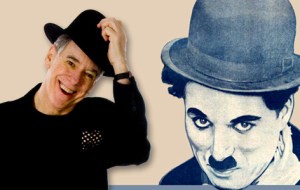

The afternoon screening also includes the 1924 Stan Laurel short comedy Detained, recently restored by Lobster Films in collaboration with the Fries Film Archief (Holland), below, where Stan’s prison release matches where Charlie Chaplin was released from prison in Police (1915), both beside the former north gate to the Los Angeles County Hospital – LAPL. Read more about them filming at the north hospital gate, and about Laurel & Hardy filming The Second Hundred Years (1927) and The Hoose-Gow (1929) at the west hospital gate HERE.

To begin, Soft Shoes depicts Harry Carey sneaking in and out of apartment buildings – the first to appear is the Bryson (lower left), still standing at 2701 Wilshire Boulevard near Lafayette Park.

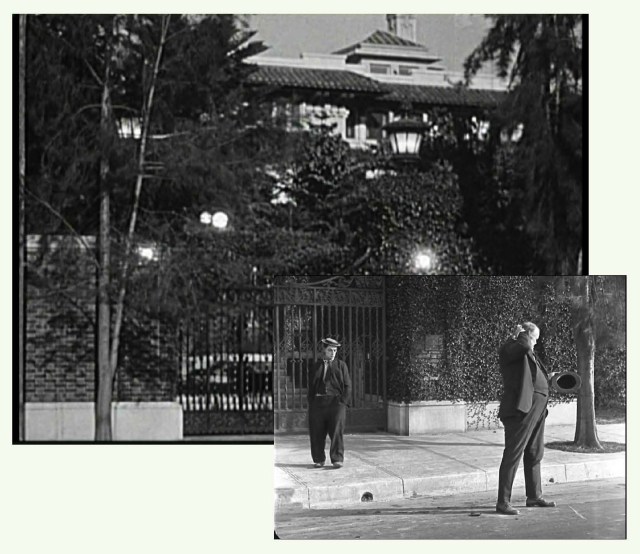

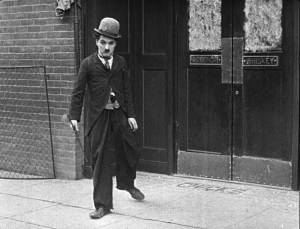

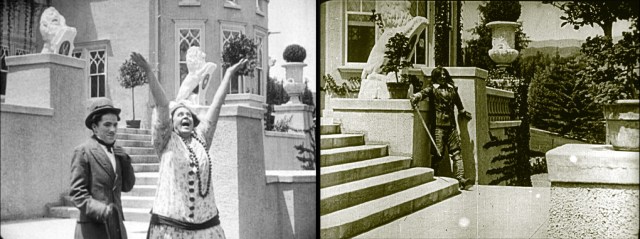

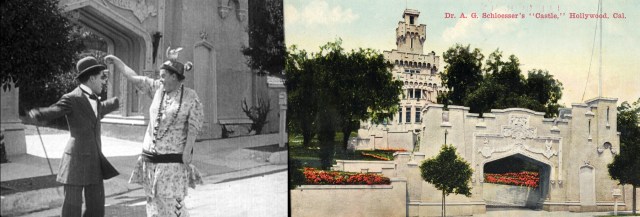

The Bryson portrayed the front of the Mack Sennett Keystone Studios, upper left above, during one of Charlie Chaplin’s earliest movies, A Film Johnnie (completed February 11, 1914, barely his second month on the job). In that film Charlie’s “Little Tramp” pesters Keystone actors as they enter and depart the “studio.” While the true Keystone studio façade actually appears in dozens of other Sennett productions, for some reason the far more impressive Bryson was employed in the Chaplin film. (Upper right –LAPL). The Bryson’s prominent front fire escape appears several times during Soft Shoes, lower left above, along with the distinctive stone lions that still guard the apartment entranceway.

The Bryson portrayed the front of the Mack Sennett Keystone Studios, upper left above, during one of Charlie Chaplin’s earliest movies, A Film Johnnie (completed February 11, 1914, barely his second month on the job). In that film Charlie’s “Little Tramp” pesters Keystone actors as they enter and depart the “studio.” While the true Keystone studio façade actually appears in dozens of other Sennett productions, for some reason the far more impressive Bryson was employed in the Chaplin film. (Upper right –LAPL). The Bryson’s prominent front fire escape appears several times during Soft Shoes, lower left above, along with the distinctive stone lions that still guard the apartment entranceway.

Built in 1913, the Bryson also appears prominently above Chaplin’s head during a scene from his Mutual comedy The Rink (1916), where Charlie meets Edna Purviance on the street at the SE corner of Wilshire Place and Ingraham (now Sunset Place). The Bryson may be best known as a setting described in Raymond Chandler’s 1943 Philip Marlowe detective classic The Lady in the Lake. Color photo Jeffrey Castel De Oro.

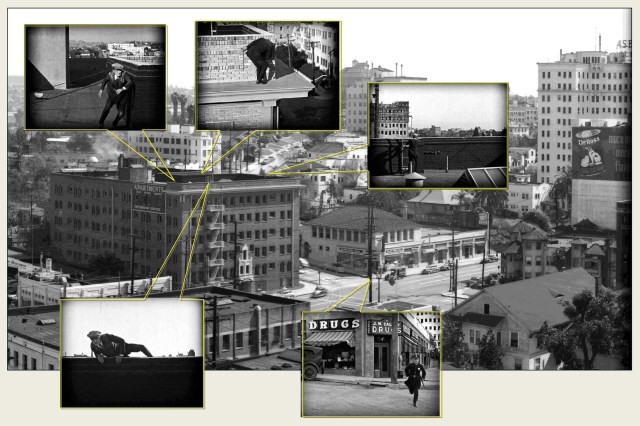

Soft Shoes also features the police chasing Harry around another high rise, including the roof, filmed at the Franconia Apartments still standing at 6th and Coronado north of MacArthur Park, pictured above facing 6th Street. The Asbury Apartments mentioned below appears to the far right. USC Digital Library.

This scene of a cop racing towards what turned out to be the Franconia contains two vital clues. At the time J. W. Calder had two corner drug stores, but only his store at 2549 W 6th Street aligned with a tall building at back. As such, this

This scene of a cop racing towards what turned out to be the Franconia contains two vital clues. At the time J. W. Calder had two corner drug stores, but only his store at 2549 W 6th Street aligned with a tall building at back. As such, this  shot above reveals the Asbury Apartments undergoing construction, which opened later in 1925, still standing at 2505 W. 6th Street. (Asbury left – USC Digital Library). By correctly assuming the rooftop scenes (click to enlarge – inset right) also depict the same Asbury Apartments under construction, triangulating back from the Asbury identified the Franconia as the primary shooting site.

shot above reveals the Asbury Apartments undergoing construction, which opened later in 1925, still standing at 2505 W. 6th Street. (Asbury left – USC Digital Library). By correctly assuming the rooftop scenes (click to enlarge – inset right) also depict the same Asbury Apartments under construction, triangulating back from the Asbury identified the Franconia as the primary shooting site.

The Franconia has a recessed fire escape shaft on each wing facing Coronado Street, put to good use as the cops follow Harry to the roof during Soft Shoes. The color image is the north wing shaft, the movie frame could depict either wing. Vintage photo Don Lynch.

Here Carey peeks north up Coronado, with buildings at back still standing. The Franconia’s decorative rooftop ledges were removed for earthquake safety reasons. Carey crouches on the south ledge of the north wing, while the camera peers across towards him from the south wing.

The view above looking NW from the Franconia roof (left) reveals a stretch of Rampart Boulevard, beginning with the Villa d’Este Apartments at 401 Rampart (A), to the corner of Rampart and W. 3rd Street (D), all appearing in Harold Lloyd’s For Heaven’s Sake (1926) (right, Harold with straw hat). As I explain in my Lloyd book Silent Visions, Harold filmed the drunken groomsmen bus scene, shown here, extensively on Rampart between 6th and 3rd, where nearly every building on the street appears onscreen and remains standing today. The Rampart corner (D) also appears in Lloyd’s Girl Shy (1924).

Below, further action takes place in Ocean Park, the small beach community south of Santa Monica.

Above left, a 1924 view east of Ocean Park, showing Ocean Front, Pier Avenue, and Marine Avenue (Huntington Digital Library). The photo documents the aftermath of the January 6, 1924 fire that destroyed the Pickering and Lick Piers. To the right, a circa 1915 view east down Pier Avenue and Marine Avenue (Huntington Digital Library). Note the church on Marine at back. The front vacant lot is where a billiard parlor (below) would be built.

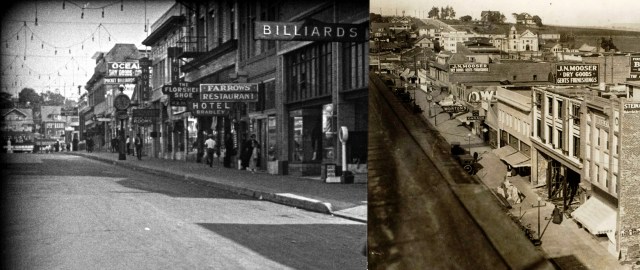

Click to enlarge. The “Billiards” building far right in the movie frame is newer, built after the photo was taken. The far right photo building says “BRADLEY” at the roof ledge, matching the Hotel Bradley in the movie frame. The J.N. Mooser Dry Goods building appears as Ocean Park Dry Goods in the movie frame. Note the matching sidewalk clock in both images.

This scene above (cropped) of Carey fleeing by automobile was filmed looking east on Pier Avenue towards Main from what was once called Ocean Front (now Neilson Way), the grand promenade that originally fronted the beach. The “FARROW’S RESTAURANT” appearing at back once stood at 130 Pier Avenue, on the ground floor of the Hotel Bradley at 130 1/2 Pier Avenue. Further back stands the Olga Hotel at 142 1/2 Pier Avenue. None of the buildings captured in this scene remain in the modern view (left).

This scene above (cropped) of Carey fleeing by automobile was filmed looking east on Pier Avenue towards Main from what was once called Ocean Front (now Neilson Way), the grand promenade that originally fronted the beach. The “FARROW’S RESTAURANT” appearing at back once stood at 130 Pier Avenue, on the ground floor of the Hotel Bradley at 130 1/2 Pier Avenue. Further back stands the Olga Hotel at 142 1/2 Pier Avenue. None of the buildings captured in this scene remain in the modern view (left).

While none of the Pier Avenue commercial buildings appearing in the movie remain today, the rear of the uphill homes still standing at 3014 and 3018 3rd Street remain visible in the far background – compare above the movie, historic photo, and modern views. (Color image (C) 2018 Microsoft Corporation).

This view looks east down Marine Street, parallel to and a block south from Pier Avenue, towards the former St. Clement’s Church that once stood on the SE corner of Washington Boulevard (now 2nd Street) and Marine. The large building at the center of the movie frame is the side of the former Masonic Temple at 162 Marine.

A closer view of the west side of the former Masonic Temple (center), and at back, the former St. Clement’s Church (LAPL), both long demolished.

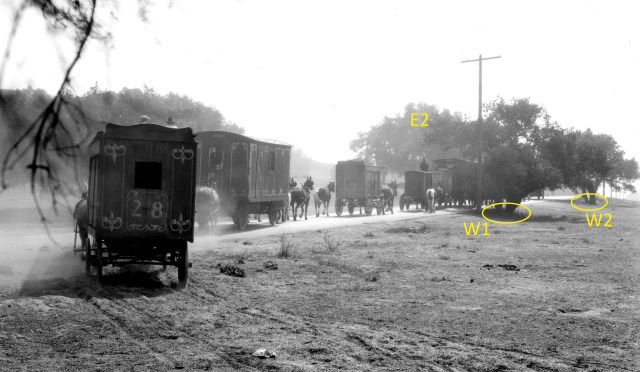

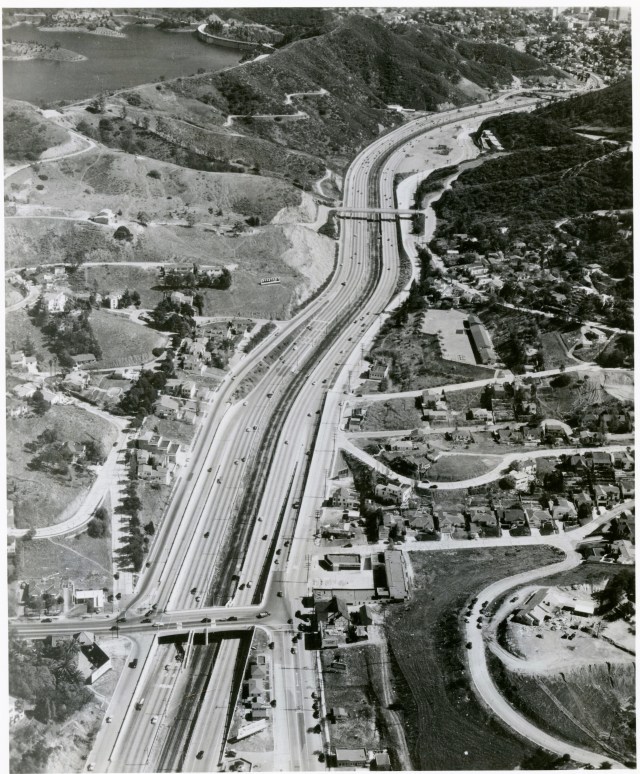

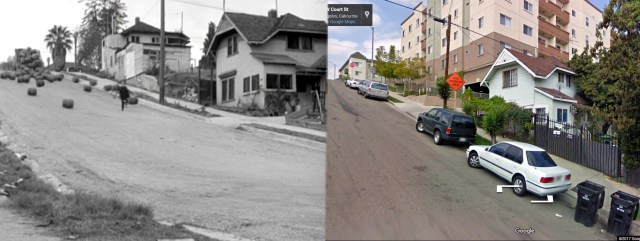

Moments later, Carey switches between cars as they pass on a steep hill, filmed just a block further east along Marine between 3rd and 4th. The retaining walls on the south side of Marine appearing in the film remain in place today. This aerial view clearly shows the Masonic Temple (box), the church (oval), and the hilly street with the retaining walls to the right (line) depicted in the film.

Moments later, Carey switches between cars as they pass on a steep hill, filmed just a block further east along Marine between 3rd and 4th. The retaining walls on the south side of Marine appearing in the film remain in place today. This aerial view clearly shows the Masonic Temple (box), the church (oval), and the hilly street with the retaining walls to the right (line) depicted in the film.

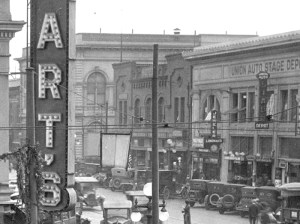

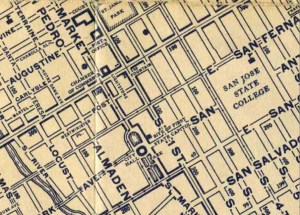

Late in the film, Carey and others run along dingy Chinatown alleys and street corners. Built in the 1880s, the original Chinatown grew east of the Plaza de Los Angeles on former grazing land owned by Mexican land baron Juan Apablasa and his son Cayetano. Denied property ownership, and restricted from living elsewhere, the Chinese suffered the neglect of their landlords, who left the privately owned streets of Chinatown unpaved. Crammed among noisy railroad tracks, towering gaswork plants, and the frequently overflowing Los Angeles River, Chinatown was the city’s least desirable address.

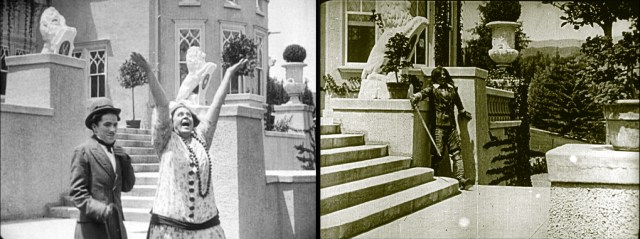

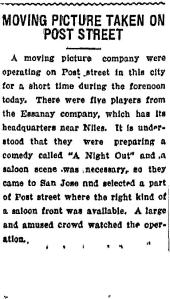

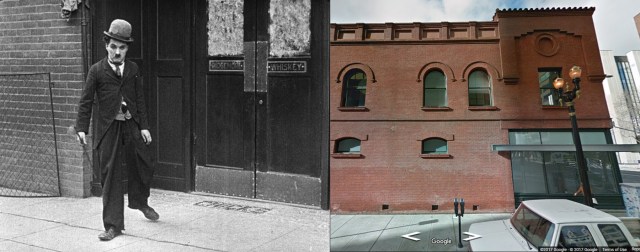

(Above, Huntington Digital Library, left, Soft Shoes upper right, Chaplin’s The Kid, lower right). Once the original leases expired, most of Chinatown was sold in 1914 to make way for the future Union Train Station. After years of litigation, the Chinese were evicted in 1934 for construction of the new terminal that opened to great acclaim in 1937. That same year community leaders formulated a master plan to develop a new Chinatown between Hill and Broadway, a mile northwest from its former site, where it remains today. Three identifiable scenes from Soft Shoes were filmed at the same spot, the corner of a narrow alley running from Marchesault Street to Apablasa Street, across from the corner of Cayetano Alley. Remarkably, one shot matches exactly where Charlie Chaplin filmed a critical scene from The Kid (1921). Here above (upper right Soft Shoes, lower right The Kid) are identical views looking south from Cayetano, across Apablasa, towards the narrow alley corner.

Above, Soft Shoes left, looking SW, a composite image from Chaplin’s The Kid, right, looking south. Both views show the same drainspout and corner alley bulletin board.

Upper left (yellow), Harry Carey runs south from Apablasa Street towards Marchesault Street, down a narrow connecting alley – this may be the only surviving image taken within this alley. Lower left (red), Chaplin at the corner of Cayetano and Apablasa. The purple arrow points west down Apablasa, matching Stan Laurel’s view, below. UC Santa Barbara c-2744_3.

A wide view looking west down Apablasa, with The Kid/Soft Shoes alley corner at the left. Stan Laurel appears at right in Mandarin Mixup (1924). Chaplin filmed Caught In A Cabaret (1914) beside the central building at back. You can read more about Chaplin and Laurel filming in Chinatown on Apablasa (below) in this post HERE.

At left, is this a happy ending for Harry Carey? Come to the festival and find out. The 2018 Soft Shoes restoration was completed by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival in partnership with the Czech Republic’s Národní filmový archiv, under the supervision of SFSFF President Rob Byrne, with SFSFF recreating English titles from the original surviving Czech print. Funding for the restoration was generously provided by the National Film Preservation Foundation with additional funding from the San Francisco Silent Film Festival Film Preservation Fund.

At left, is this a happy ending for Harry Carey? Come to the festival and find out. The 2018 Soft Shoes restoration was completed by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival in partnership with the Czech Republic’s Národní filmový archiv, under the supervision of SFSFF President Rob Byrne, with SFSFF recreating English titles from the original surviving Czech print. Funding for the restoration was generously provided by the National Film Preservation Foundation with additional funding from the San Francisco Silent Film Festival Film Preservation Fund.

All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission. HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. The Kid – Criterion Collection; Chaplin’s Mutual Comedies; The Stan Laurel Slapstick Symposium Collection Volume 2, Eric Lange and Serge Bromberg, Lobster Films; Chaplin at Keystone Collection, Lobster Films for the Chaplin Keystone Project. Except where noted color images (C) 2018 Google.

Below, the Franconia Apartments.